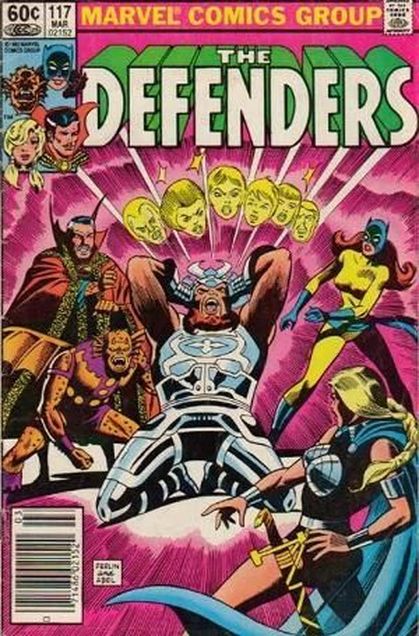

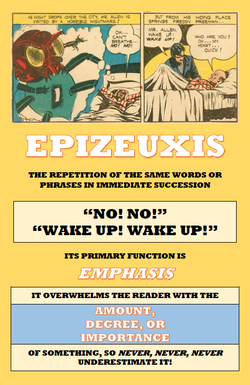

We're not kidding ... it's the coolest Now that my summer of writing, editing, and reviewing has ended with two weeks of eating Butterbeer ice cream on the steps of Gringotts Bank inside Diagon Alley, I thought I'd be in the best frame of mind to share with you the coolest activity you can do with a comic book. I first shared the idea at the 2014 Reading for the Love of It Conference back in February and it generated a lot of positive feedback. The idea, however, is very simple. So many of the activities that are built around visual narrative in the classroom have teachers getting their students to create a graphic novel or story out of some other work they are doing. For example, students are asked time and again to "Choose a favourite moment" in a novel they are studying and turn it into a graphic story. They are often told how many panels should be on the page and are reminded to use dialogue bubbles and narrative boxes in their story. There's nothing wrong with this activity once in a while. It serves a purpose. However, if teachers are really wanting students to understand something about a novel, poem, or play, and think that comics can help, then the opposite activity is much better: Have students take a comic book and get them to transform it into the form they are presently studying. What this activity teaches students is that novelists must rely exclusively on words to present a whole range of complex ideas, emotions, and situations. Since graphic novelists use pictures, and pictures (as we know) tell a thousand words, how cool is it that novelists can create these in our head without a visual component to their narrative? Let's say I wanted to use graphic storytelling in teaching Dickens' Great Expectations. Sure, I could ask students to "visualize" the opening scene by creating a graphic narrative about Pip's encounter with Magwitch. Will this teach students something about the impact that Dickens' words have on what they imagine? I suppose it will, although students who are self-conscious about their artistic skills might suggest they can't adequately represent what's in their head. However, I am much more inclined to take a comic like issue #117 of The Defenders--one that begins with a group of superheroes gathering in a storm-swept glade in upstate New York to commemorate a fallen comrade--and get them to turn it into what could be the opening of the novel. Sure, they can incorporate some of the narrative captions and dialogue featured in the comic--these will prove to be useful scaffolding--but they are going to have to use language to describe the visual landscape of the comic. This gives students a hands-on activity that really teaches them something about novel writing rather than about graphic storytelling. If you want students to learn about a particular literary form, then, have the work they are producing be of the form you want them to learn about about. If you enjoyed this activity, you might also enjoy:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Glen DowneyDr. Glen Downey is an award-winning children's author, educator, and academic from Oakville, Ontario. He works as a children's writer for Rubicon Publishing, a reviewer for PW Comics World, an editor for the Sequart Organization, and serves as the Chair of English and Drama at The York School in Toronto. If you've found this site useful and would like to donate to Comics in Education, we'd really appreciate the support!

Archives

February 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed