COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS

Anyone interested in teaching, learning about, or more fully understanding and appreciating the range of visual narratives waiting to be explored would do well to take a close look at the titles below. These are some of the best and most groundbreaking efforts of the past 75 years.

The Mysterious Underground Men (1948), by Osamu Tezuka

Although we sometimes think of New Treasure Island (1947) as the first manga comic, Osamu Tezuka's The Mysterious Underground Men is the one that the author himself considered the first of his "story manga." It tells the tale of Mimio the Rabbit who tries desperately to prove his humanity while helping his friends deal with mysterious creatures under the earth dead set on taking over the surface world. The work is amusing, exciting, and, in the final analysis, heartbreaking, serving to shape with its ending the course of manga in the nearly 70 years since its publication.

A Contract with God (1978), by Will Eisner

Generally considered to be the first graphic novel in the North American tradition, this 1978 classic by Will Eisner showed a generation of readers comics something that they had forgotten: that it did not simply have to be the Sunday funnies or feature an assortment of costumed crusaders. Eisner sets his collection of stories on the fictional Dropsie Avenue in the Bronx, and what he achieves in telling stories of the very real human dramas that unfold every day on our city streets--stories of triumph and of tragedy--changed the course of comics history. In some ways, A Contract with God is peerless in the canon of visual narrative, and is a must read for anyone undertaking a serious study of the genre.

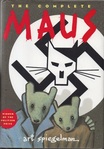

Maus (1986), by Art Spiegelman

If you are an educator who has taught a full-length graphic novel in your middle or high school English classroom, the overwhelming chances are that you taught Art Spiegelman's Maus. Telling the story of Spiegelman's father as a Holocaust survivor during the war, the novel uses the ingenious and sometimes controversial device of anthropomorphized animals. The story is not only about the horrifying experiences of Spiegelman's father, however, but about the relationship between father and son that develops over the course of the novel, and the latter's efforts to tell his father's story as a visual narrative.

The Dark Knight Returns (1986), by Frank Miller

Few would argue that The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller is the single most important Batman story ever told. It is ten years after an aging Batman has retired that the crime and violence on the streets of Gotham are in desperate need of his glorious return. With Carrie Kelly, a female Robin at his side, Batman must work to defeat rival mutant street gangs, face off against two of his greatest foes--the Joker and Two-Face--and then go up against his longtime ally, Superman, in a battle that only one of them can survive. The Dark Knight Returns is often seen as being almost singlehandedly responsible for the resurgence of interest in Batman and for the film franchise that followed.

Watchmen (1986), by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

One can't underestimate the importance of Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. A decade ago, Time Magazine compiled a list of the Best 100 novels from 1923 to the present, and Watchmen was on it. Powerful, compelling, and complete with characters who burn into the retina of our collective memory, this graphic novel simply must be read by any student of the genre. Chronicling the fall from grace of aging superheroes, this Hugo-Award winning graphic novel is one of the most frequently studied works of visual narrative in the postsecondary academy. It also underscores the profound contribution to the genre by creative genius, Alan Moore.

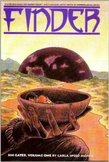

Finder (1996-present), by Carla Speed McNeil

With her webcomic Finder, Carla Speed McNeil introduced us to the remarkable world of her wandering protagonist, Jaeger. In the first volume of the series, Jaeger becomes involved with a family trying desperately to recover after escaping a psychologically abusive father. Although McNeil chooses a science fiction setting for her series, her characters are all too human in their depth and complexity, and the series itself explores important issues about family, identity, and the self. The series has garnered no small amount of critical praise across the various volumes that have been published in web and print form over the course of the last two decades. Finder is, when all is said and done, a superlative achievement.

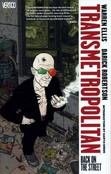

Transmetropolitan, Volume 1 (1997), by Warren Ellis and Darcik Robertson

The brainchild of the irrepressible Warren Ellis, Transmetropoltian, Volume 1: Back on the Street tells the story of Spider Jerusalem, an investigative reporter living in the 23rd century who returns from his self-imposed exile to a civilization whose corruption and degradation drove him away in the first place. Now, as a reporter for The Word, Jerusalem sees it as his mission to confront the injustices of his society in the way only he can. As a post cyberpunk comic, Transmetropolitan speaks volumes about how Ellis sees our ultimate salvation not in the hands of costumed heroes with superhuman powers, but resting with the common man willing to stand against the forces of corruption.

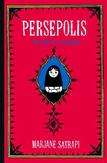

Persepolis (2004), by Marjane Satrapi

Educators who have taught a graphic novel at the high school level that was not Art Spiegelman's Maus have likely taught Persepolis, the compelling graphic narrative by Marjane Satrapi that chronicles her life in Iran at the time of the 1979 revolution. With her we see the revolution through the eyes of a child who must very quickly grow up, confronted as she is with the terrifying events that shaped the country she loved so much. What is so profound in Persepolis, however, are the important things it has to say about family, and about how it can be the only thing to hold onto when the rest of the world is going crazy. Satrapi's use of the symbolic is an especial strength of the narrative, as is her understanding of the limitless potential of the visual in telling such a story.

Building Stories (2012), by Chris Ware

Hands down the best graphic novel of 2012 and arguably the best novel of 2012, Chris Ware's Building Stories is in some ways difficult to fathom. Developed and written over the course of ten years, the novel is comprised of a series of fourteen differently formatted, sized, and bound pieces that tell an interconnected series of stories from a Chicago three-flat occupied by a curious cast of characters. Building Stories garnered four Eisner awards on its own and was on the Top 10 book lists of most major reviews, including the New York Times, Time Magazine and Publishers Weekly.

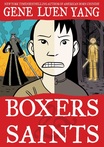

Boxers & Saints (2013), by Gene Luen Yang

Many had Boxers & Saints on their list of the Best Graphic Novels of 2013 and with good reason. This pair of graphic novels tells the story of the Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the 20th century. Told from the perspective of a young person on either side of the conflict, it shows the world the immense talent of Yang, who previously impressed with American Born Chinese. In Boxers, Little Bao, a Chinese peasant boy, grows up to lead his people against the Christian influences that he sees as threatening his homeland. In Saints, Vibiana must decide whether to remain true to her Christian faith or abandon it in favour of rebellion.