VIDEOS

There are so many great videos out there just waiting for you to share them with your students. The trick, sometimes, is finding them. While I enjoy sifting through countless videos on YouTube that are student reenactments of great works of literature, I would prefer to know what's out there in advance. What follows is a collection of great YouTube videos that are either animated or focus on visual narrative in some way. They can really help you make successful curriculum connections with your students and help foster engagement.

|

|

I Heard a Fly Buzz When I DiedI heard a Fly buzz -- when I died --

The Stillness in the Room Was like the Stillness in the Air -- Between the Heaves of Storm -- So begins Emily Dickinson's "I heard a Fly buzz -- when I died --," a chilling poem that focuses on one of her favourite themes: Death. Even more chilling, perhaps, is this 1989 adaptation of the poem by Lynn Tomlinson. Here, the incessant buzzing and shifting, animated canvas seem spot on with Dickinson's own sensibilities. |

When I teach this poem to my IB English students, I find Tomlinson's video to be eminently helpful. Above and beyond generating great discussions about the mood that it establishes, the video also shows students that the poem really works best when it's subject to a very matter-of-fact reading. So much of Dickinson's poetry is like this in fact. I really love the way the poem is delivered, especially when the fly appears on the scene. It takes students no time at all to realize that the windows failing are the speaker's eyes, and then they soon discover that nearly every time Dickinson makes reference to windows, our ocular faculties are in play. Soon after, they make the connection between "Eye" and "I" that pervades so much of Dickinson's writing.

Some educators would argue that the video serves to interpret the poem for students--that they have less of an opportunity to think or to imagine by virtue of watching it. This, however, is a red herring, because young learners profit far more from listening to a solid reading of the poem first and seeing it in some sort of context. We don't go to a performance of Hamlet and come away complaining that the director ruined Shakespeare's text by interpreting it (unless, I suppose, the interpretation is dreadful). We don't fret about the sanctity of a screenplay for a film when we go and see the film at the theatre.

As educators, we need to get away from handing out the poem to students, asking Sally to read it (because Sally likes reading out loud) and then asking the class what the poem means. That stopped being cool last century.

Some educators would argue that the video serves to interpret the poem for students--that they have less of an opportunity to think or to imagine by virtue of watching it. This, however, is a red herring, because young learners profit far more from listening to a solid reading of the poem first and seeing it in some sort of context. We don't go to a performance of Hamlet and come away complaining that the director ruined Shakespeare's text by interpreting it (unless, I suppose, the interpretation is dreadful). We don't fret about the sanctity of a screenplay for a film when we go and see the film at the theatre.

As educators, we need to get away from handing out the poem to students, asking Sally to read it (because Sally likes reading out loud) and then asking the class what the poem means. That stopped being cool last century.

Learning to See the Social: How to Read a Graphic NovelIn this excellent TEDx talk by Dartmouth College Associate Professor, Michael Chaney, he talks at length about the form and structure of graphic novels and how understanding these things allows us to make meaning of visual narrative and derive a fuller appreciation of it. One of the graphic novels he talks about at some length is Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis. I've used this TEDx talk with students when teaching the graphic novel because it shows students how much depth we can get into in just the first two panels of the story!

|

|

Chaney also gets into the whole idea of how we tend to process cartoonish representations of the human form in a different way than we would still photography. Photography suggests an image captured in the a past that no longer exists. We know that something in a photograph is not happening to the person "in the here and now" because the photo had to have been previously taken. However, Satrapi's cartooning shows us a character that we, as readers, are willing to believe is in "the present" of the narrative. This is such an insightful idea and one that can generate really excellent discussions with students.

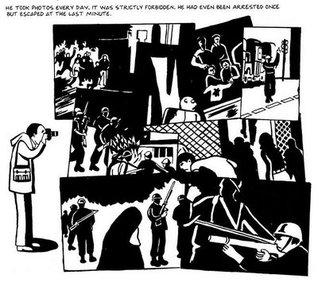

Chaney's talk and the ideas it raises also allow for a lot of cross-polination depending on the other writers your students are studying. For example, Margaret Atwood's poetry is filled with references to the problematic nature of photography: how photographs capture an instant in time, but don't tell us what happened to the subject in the time before or the time since the click of the camera's shutter. Think, for instance of "This is a Photograph of Me" or "Girl and Horse, 1928." Satrapi also focuses on photographs as a visual record, with a memorable full-page panel of her father taking photos of the violence, and other panels in which a character is looking at a photograph from the past and pointing out something about it.

Chaney's talk, then, is a wonderful starting point for such discussions. Be sure to check it out!

Chaney's talk and the ideas it raises also allow for a lot of cross-polination depending on the other writers your students are studying. For example, Margaret Atwood's poetry is filled with references to the problematic nature of photography: how photographs capture an instant in time, but don't tell us what happened to the subject in the time before or the time since the click of the camera's shutter. Think, for instance of "This is a Photograph of Me" or "Girl and Horse, 1928." Satrapi also focuses on photographs as a visual record, with a memorable full-page panel of her father taking photos of the violence, and other panels in which a character is looking at a photograph from the past and pointing out something about it.

Chaney's talk, then, is a wonderful starting point for such discussions. Be sure to check it out!

|

|

Changing Educational...er... Visual ParadigmsMost educators by now have seen Sir Ken Robinson's famous TED Talk, "Changing Educational Paradigms," the most watched of such talks in history. Many have also seen the video presented here that shows the RSAnimate version of the talk. I showed it recently to my students before they worked on a visual note-taking activity that I blogged about a couple of days ago ("Visual Narrative Meets Note-Taking"). No doubt if I had shown the version with just plain old Sir Ken they would have enjoyed it enough.

|

But the animation is just so entirely engaging in this video -- it provides so much to both the visual and auditory learner alike -- that it speaks volumes to teachers about our need to give students opportunities to put their thoughts down on paper in a way that makes sense to them. We can get them to organize their ideas to form a coherent comparative essay later, but for now it is so much better to allow them to express their understanding in a way that looks more like the thoughts themselves and less like some linear model that does not mimic how they think. This is the beauty, I think, of something like RSAnimate. It shows us a kind of visual note-taking that is rich, powerful, and inspiring--exactly what we want our lessons to be.

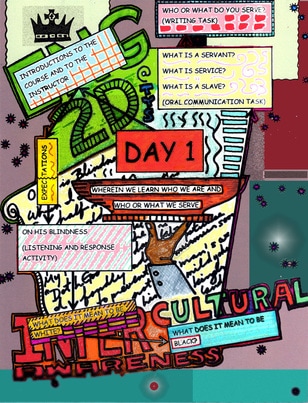

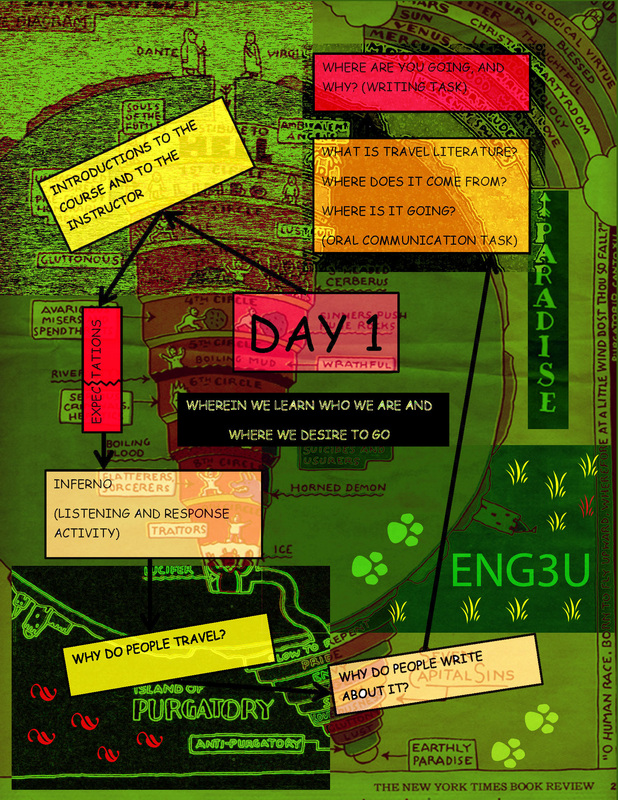

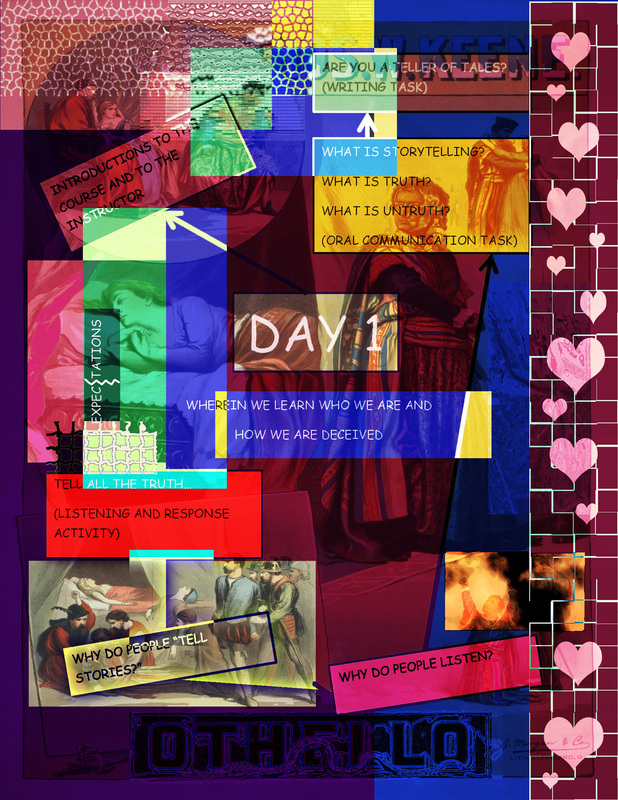

I won't repeat my previous post by sharing Catherine's work with you, but I will show you my own. Inspired by the RSAnimate version of Sir Ken's talk many moons ago, I decided that my lesson plans needed to have something of the visual in them. So, I started creating lessons that would use a hybrid of comic book narration bubbles, a flow chart, and visual imagery. Throw in some colour and a pinch of Photoshop and you have an array of visual lesson plans that students will respond to.

I won't repeat my previous post by sharing Catherine's work with you, but I will show you my own. Inspired by the RSAnimate version of Sir Ken's talk many moons ago, I decided that my lesson plans needed to have something of the visual in them. So, I started creating lessons that would use a hybrid of comic book narration bubbles, a flow chart, and visual imagery. Throw in some colour and a pinch of Photoshop and you have an array of visual lesson plans that students will respond to.

Every year at least one student asks me why I do this. Is it that I'm just such a comics fanatic that I have to do visual lesson plans in this way? Do I have hours of time to spend on these aesthetic touches?

"No," I tell them. "I do this because learning is beautiful."

"No," I tell them. "I do this because learning is beautiful."