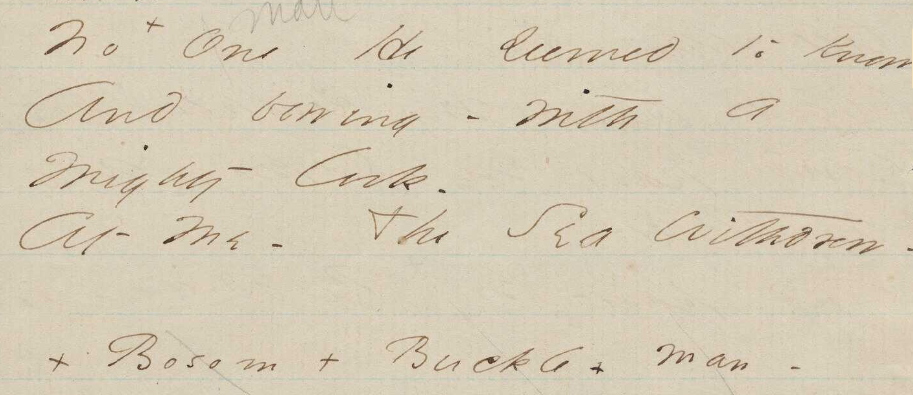

Sometimes Literary Analysis Takes You Down the Rabbit Hole After Shakespeare and Dante, my pick for the greatest writer of all time is Emily Dickinson. She's been my choice for a long time, despite the fact that Tolstoy, Joyce, Chaucer, Wordsworth, Moliere, Montaigne, Milton and Austen often round out critics' Top 10 lists. I tend to agree with Harold Bloom, though, who sees Emily Dickinson as the greatest literary genius since Shakespeare. As it turns out, just about the craziest set of circumstances occurred that led me to what I'm hoping is a neat discovery in one of Dickinson's poems. I was preparing some notes for my class on "I started Early, took my Dog," a poem in which an unnamed speaker appears to have an amorous encounter with the sea. Some critics steer clear of making too much of this, while others--pardon the pun--wade in well past their waist. Here is the poem, complete with Dickinson's original spelling: I started Early – Took my Dog – Dickinson certainly wasn't shy about expressing these kinds of feelings in her poetry. Consider a poem like "Wild Nights, Wild Nights!" for example. Students find this interesting about Dickinson, especially since they often see her as a poet whose focus is typically nature, death, or the precariousness of the human mind. As I was making notes on the poem, however, I suddenly remembered my copy of The Graphic Canon, Volume 2, edited by Russ Kick. I knew it had a couple of Dickinson poems and thought it might be cool to show my students one of them at some point during our unit. Although it doesn't have "I started Early, took my Dog," the anthology does contain versions of "Because I could not stop for Death" and "I taste a Liquor never brewed." Inspired by the visual re-imaginings of these poems, I began doing some visible thinking about "I started Early took my Dog." These were just doodles really, and pretty soon I was buried in The Graphic Canon again, this time looking at Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky." But that's when the weirdness happened. I noticed I had circled the words "No man" in line 9 and "no one" in line 22 of the poem when I suddenly remembered the scene in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass where Alice sees "Nobody" and the White King tells her she has great eyesight. Then I remembered something else: that Odysseus refers to himself as "Noman" when he blinds Polyphemus the Cyclops in The Odyssey. "Wow, I thought to myself, wouldn't it be cool if Dickinson was playing with the whole idea of Odysseus' name in line 9?" After all, she treats the nobody-being-a-somebody idea in her poem, "I'm Nobody! Who are You?" When I asked my students in class the other day if they could spot the name of a mythological character in "I started Early, took my Dog," it only took a short time before one of them, Marina, replied with "Noman." After class, I was sitting down with my colleague, Chloe, at The York School and we were discussing the poem. I was explaining this idea, noting, for instance that the dog in the poem is mentioned in the first line and that it then completely disappears. I know from the iconography of visual art that a dog can represent fidelity, so perhaps its disappearance is suggesting an unfaithfulness on the the part of the speaker. Perhaps she's already involved with someone, and her encounter is something like an imagined affair with the sea god, Poseidon... If the above observations are accurate, then, all of this leads to a rather startling conclusion: The speaker of the poem must be Penelope, the wife of Odysseus. Odysseus left his dog, Argos, behind when he went he went off to fight in the Trojan War. I know this because as Chloe and I were discussing the poem I looked it up. When Odysseus returns and disguises himself in order to avoid detection by Penelope's suitors, he discovers that Argos has been neglected by the women, and has been left to spend its time lying on a dung heap. When Odysseus approaches him, Argos, the faithful dog, recognizes his master. However, Odysseus has to ignore the dog so that he doesn't give away his true identity. So, he sheds a tear before walking past Argos without acknowledging him. Argos, having fulfilled its purpose of remaining faithful to Odysseus until his return, dies. So, when Dickinson's speaker says, "But no Man moved me" she could be saying that the tide was the first thing that "moved her," but she could also be saying that before the tide, "Noman"--that is, Odysseus--moved her. The entire poem could be a kind of elaborate imagined fantasy in which Poseidon and Penelope have this passionate encounter. The language and imagery of the poem are extraordinarily suggestive, as numerous critics have pointed out, but there was one remaining point about the Penelope theory that confused me. If Dickinson had indeed intended to use "no Man" to suggest "Noman," why does she write in lines 21 and 22, "Until we met the Solid Town / No one he seemed to know"? Another student pointed this out in our last class, and I bemoaned the fact that she used "one" here. If my idea of the speaker as Penelope is correct, it seems strange that Dickinson didn't think of saying, "No Man he seemed to know." Except, of course, that Dickinson DID think of this, as I discovered late last night! Take a look at the original copy of her work and the marginalia that accompanies it from the Dickinson archive: That's right...if you look closely you can see the plus sign after "No" and even the word "man" lightly penciled in beside it. Then, following the plus sign, we see at the bottom that she considered using "Man" instead of "one." (She thought of using "Bosom" and "Buckle" to replace "Bodice" by the way.) So, thanks go out to Russ Kick's The Graphic Canon, Volume 2, my colleague, Chloe, at The York School, my exceptionally clever students, and even a former colleague from UBC, Adam Frank, who was kind enough to let me know he hadn't heard of the interpretation before but thought it might be a good one. Dickinson always surprises me, even when I know that she will always surprise me. I don't think you can ask much more of a poet.

0 Comments

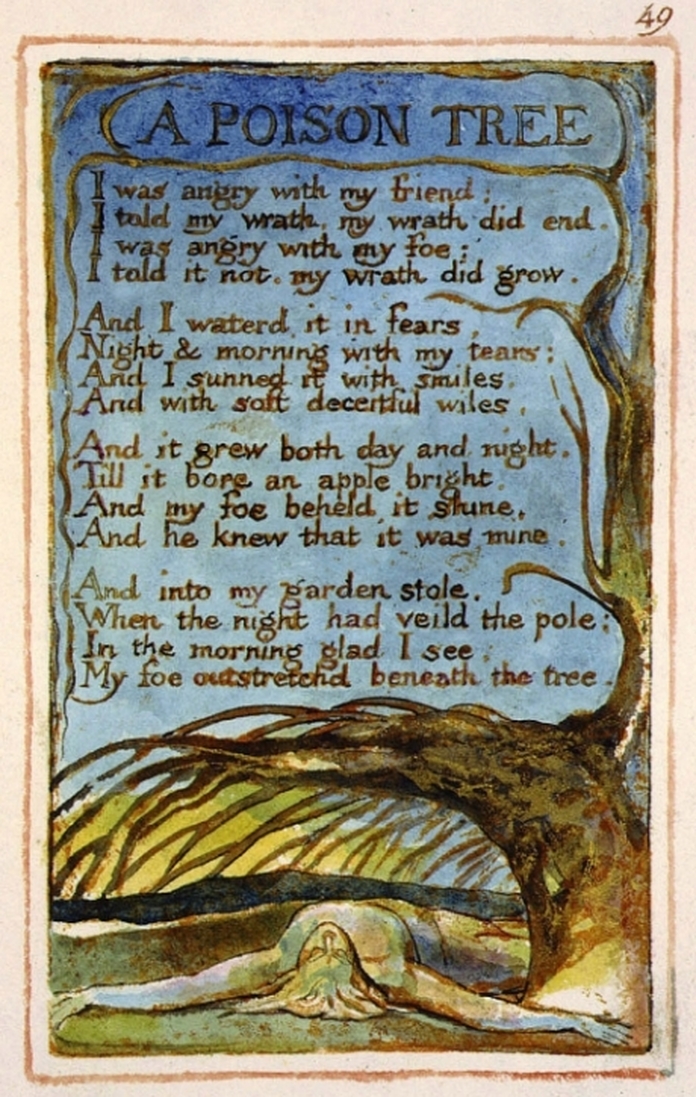

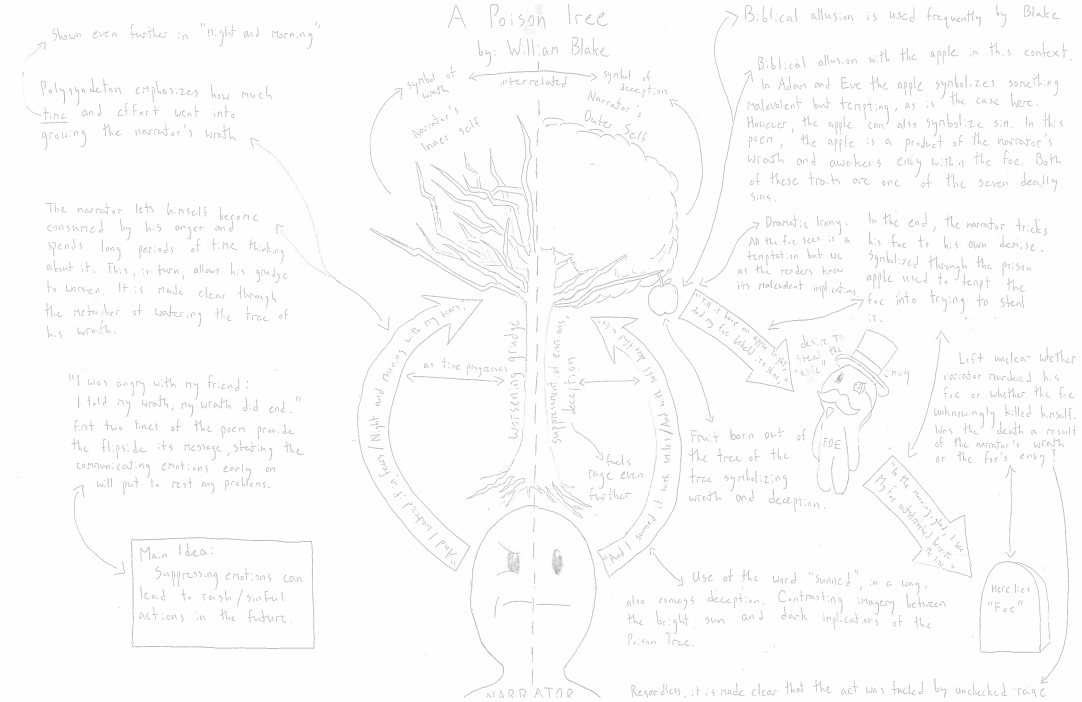

One of the more disturbing poems in Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience, "A Poison Tree" taps into the tradition of the mythologized apple just waiting to bring down whomever should happen to pick, receive, accept, or otherwise agree to get their hands on it. The speaker in "A Poison Tree" recognizes that he is prone to anger, but that he can govern such feelings and bring them to a peace when he is dealing with his friends. Not so much, however, when he's dealing with his enemies. As we can see from Adrian's visual brainstorming exercise below, there is so much going on in this poem: Of course, with this kind of visual brainstorming activity, it's not the physical amount of text or number of illustrations that is of significance; rather, it's the quality of insight. The slideshow below, shows us, indeed, the kind of quality we're hoping for. If you haven't had an opportunity to try visible thinking with your students, a poetry unit is a great opportunity to do so. Get students to show you what they are thinking--by any means necessary--and you might be surprised what you find. If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy...

|

Glen DowneyDr. Glen Downey is an award-winning children's author, educator, and academic from Oakville, Ontario. He works as a children's writer for Rubicon Publishing, a reviewer for PW Comics World, an editor for the Sequart Organization, and serves as the Chair of English and Drama at The York School in Toronto. If you've found this site useful and would like to donate to Comics in Education, we'd really appreciate the support!

Archives

February 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed