|

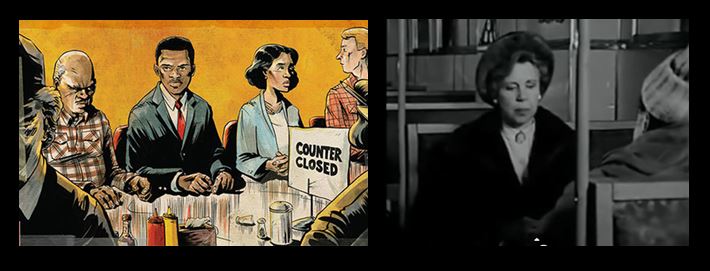

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com When It Comes Right Down to It, There's Nothing Like Adam Davidson's "The Lunch Date"This past year I was inspired by John Lewis and Andrew Aydin's March, Book 1 to consider what the best work of visual narrative or visual media would be to support teaching students about race and race-related issues in the K-12 classroom. For instance, if I were teaching Kathryn Stockett's The Help, or Shakespeare's Othello, or the speeches and writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., what would be the best supporting piece of visual narrative or media I could use? Would it be Prom Night in Mississippi? What about Guess Who's Coming to Dinner or Do the Right Thing? The answer isn't easy. Lewis and Aydin's book is amazing, as is Mark Long and Jim Demonakos' The Silence of Our Friends. Both of these are exceptionally compelling graphic novels and among the best books of their respective years. However, if I had to choose, I'd go with a piece I've done so many times with my students: Adam Davidson's 1989 short film, The Lunch Date, winner of the 1990 Short Film Palm D'or and the 1991 Academy Award for Best Short Subject. I could spend quite a bit of time here explaining to you the brilliance of Davidson's film and what its implications might be for your classroom. Just watch it, however, and be prepared to be absolutely blown away.

1 Comment

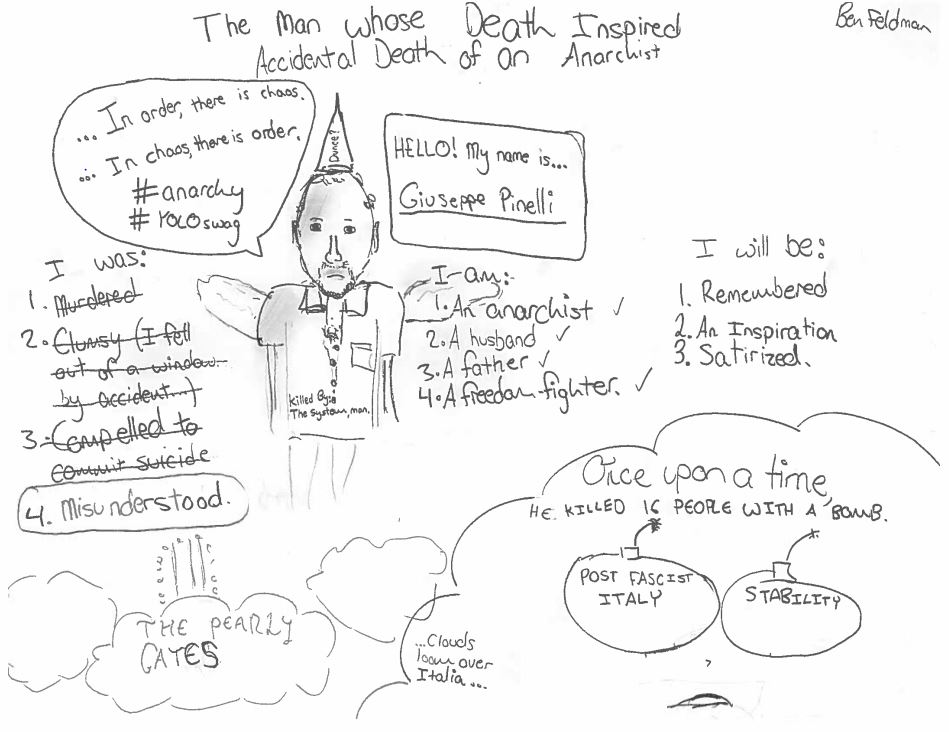

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com Visual Brainstorming Once Again Proves Its WorthI love this recent example of visual brainstorming submitted by my student, Ben. It's the product of a short article he read about Giussepe Pinelli, an anarchist whose death was the inspiration for Dario Fo's Accidental Death of an Anarchist, which I blogged about a couple of days ago. There are so many wonderful touches here that bring together a diverse array of cultural phenomena, including comics, social media, and good old-fashioned brainstorming.

The dialogue balloon, "In order, there is chaos... In chaos, there is order. #anarchy #yoloswag," wouldn't look out of place by any stretch in the Twitterverse, but neither would his lists look out of place in a free-writing or brainstorming assignment. Somehow, the comics-inspired illustrations bring it all together, and blend historical events with Pinelli's own view of himself in an insightful visual brainstorming exercise. What blows me away, however, is the crossed-out list on the left hand side of the paper. So many times as teachers we encourage students to cross out and continue when they make a mistake rather than white something out or erase. We are very wise for telling them this! Not only is it a time saver, but teaching kids that it's okay to cross out pays dividends in a situation like this in which the crossing out becomes a rhetorical strategy that shows a deep understanding of the circumstances surrounding the play and the underlying themes of the play itself. We can't get to the bottom of the mystery about what happened to the ill-fated anarchist. The only thing we can be sure of is that he was very likely misunderstood. So, as I've been saying over the last few weeks since starting this blog...Do this exercise with your students. You'll be so glad that you did! by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com We're Blushing for Goodness Sake...We wanted to take a moment to thank you once again for your support of this site. We have only been in operation for a very short time, but we've already made connections with some wonderful educators out there. Receiving 50,000 visits in little more than two weeks is very flattering, but here at Comics in Education we'd like to think it has to do with one basic idea.

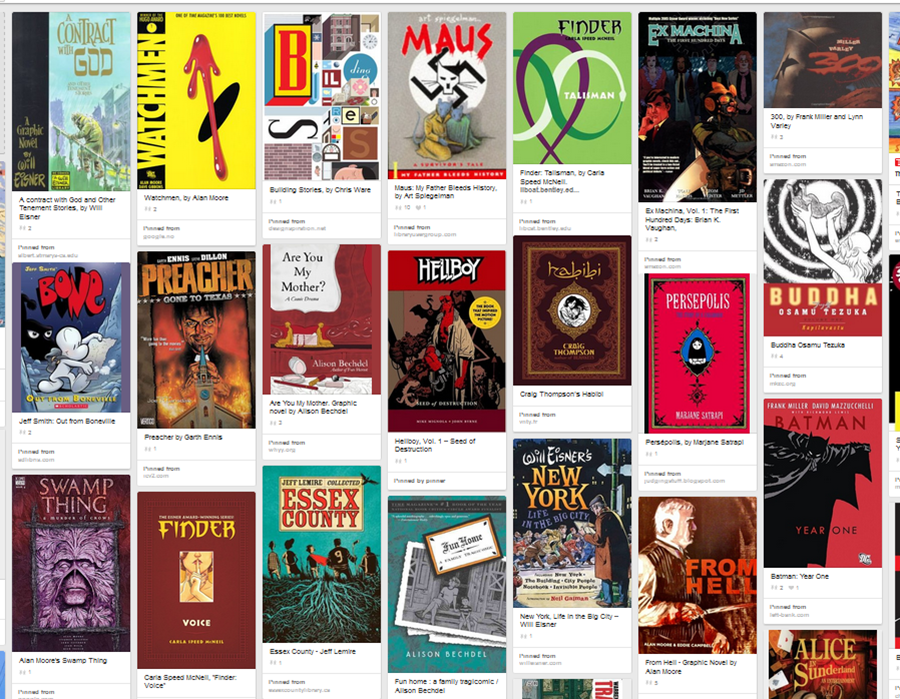

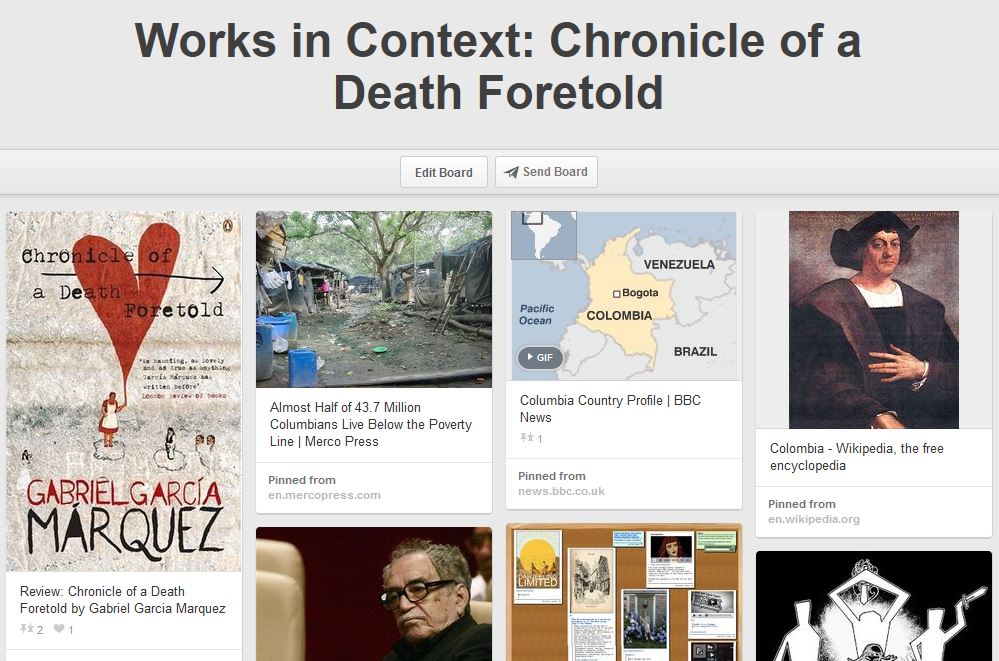

We want to foster and develop a love and appreciation for visual narrative in the K-12 classroom. We want educators--all educators--to see that comics and graphic novels represent a genre worthy of study, that they have a tradition, and that they can open up a young person's mind to different ways of seeing and interpreting the world around them. They can encourage a reluctant reader to read. They can encourage a second language learner to acquire a new understanding of the language they are learning. And they can help students to make connections among a wide variety of texts, whether literary, artistic, or cultural. So many of you out there are doing wonderful things in comics and in education. We can't wait to see what you do next! by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com Build Pinterest Boards For Comics Research. Then, Build Them to Research Anything!If you want to put a great tool in the hands of your class and happen to be teaching them visual narrative, it would be hard to go wrong with Pinterest. No longer thought of merely as a repository for folks who want to collect pin board after pin board of flower arrangements or dinnerware, Pinterest has become a valuable tool in the hands of an educator. If you want to give students a quick primer on some of the great comics and graphic novels that are being written, why not have them do searches for comics and graphic novels on Pinterest. They'll literally find thousands of boards where people have pinned their favourite comics and graphic novels. (I've even put together boards called Graphic Novels for Kids, Literacy Resources for Students, and The Best Graphic Novels of All Time.) However, students can refine their searches as well in order to find, for instance, the comic or graphic novel they are studying. Perhaps the Pinterest image will take them to a website that might help them learn more about the work they are studying. If you're teaching the class, however, you can build your own boards and gather images that have links to great resources! I've done precisely the same thing with my Grade 11 students. While studying, for example, Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, I have them go to my Pinterest site. They can click on these images and the images will then take the students to sites that have valuable contextual knowledge for the study of Marquez's novel. Visual learners love this since they learn both from the images themselves as well as the content they ink to. It's such a valuable process that I've now created a Pinterest portion of this website. If you want a simple way of ensuring that you can come back to a blog post without having to search for it through the archives or the list of categories, go to the "Go For a Pin!" folder under the Contact tab. It lets you pin images from the blogs to your site. When you click on these in the future you'll come back to the blog that the image came from! Ultimately, this post is just to whet your appetite in terms of the pedagogical uses of Pinterest. I can already see the wheels in your head turning, however. Some great possibilities, right?! Comics in Education 2.0

3/28/2014

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com A Quick Timeout to Show You A Few Updates to the Site!We hope you've been enjoying Comics in Education and wanted to let you know about a few changes we've made. The landing page has switched to our blog since so many of you are visiting it. The home page, though, has seen a radical makeover and now features ten very handy buttons to take you to places you want to go! It will also feature news and other important updates, so be sure to check back regularly. As we make changes and updates we'll keep you posted. If there are any changes we can make so your experience on the site is more enjoyable, just let us know through a contact form! This is what's in your student's head...

3/28/2014

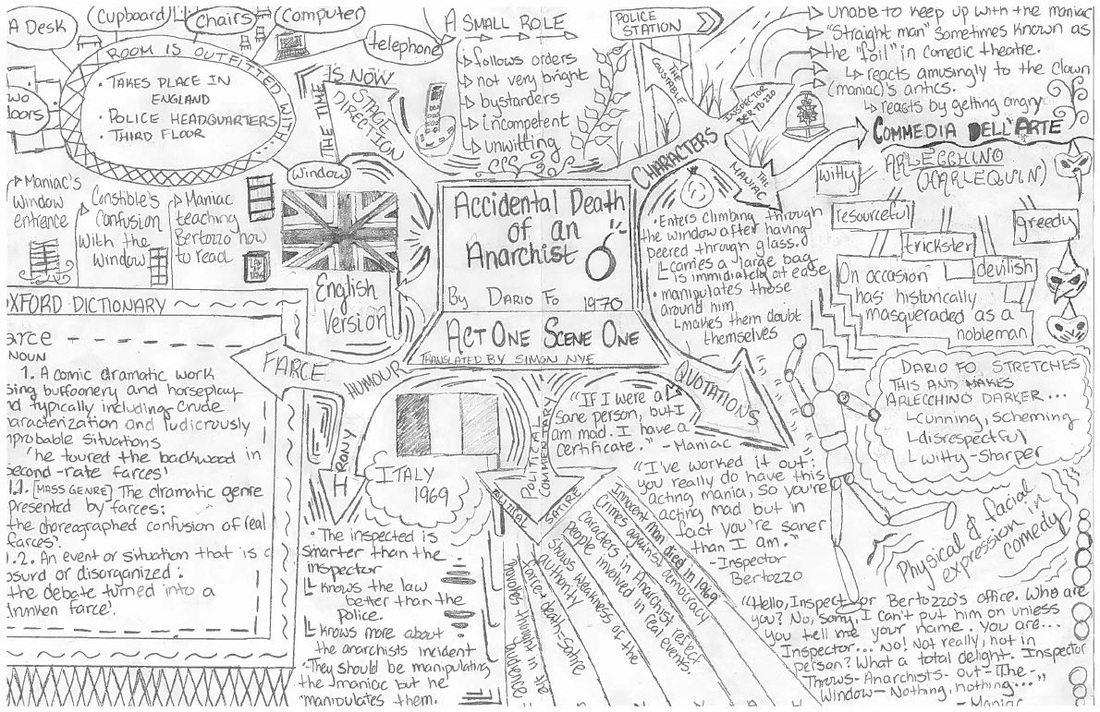

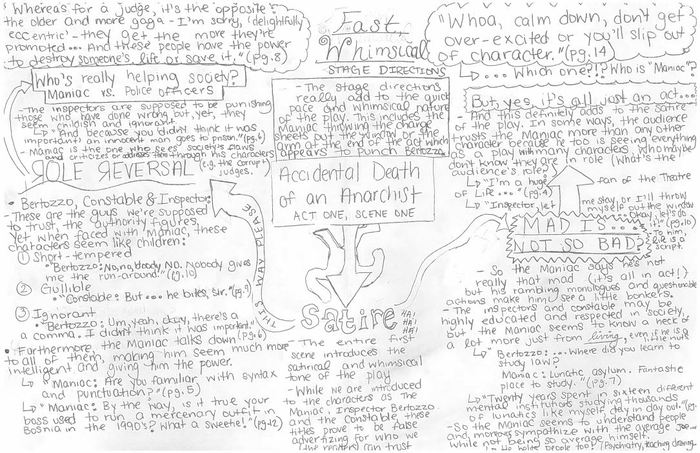

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com The trick, of course, is getting it to come out!For those who are yet to be convinced of the power of visual brainstorming, or who are wondering why teachers haven't all been doing this since the first time students were made to sit down in chairs and listen to grown-ups in school, I present to you this latest effort. It comes from my student, Hannah, who apparently had quite a lot to say about Dario Fo's Accidental Death of an Anarchist. I'm not really sure what to call this one. "Crazy Town" comes to mind, I think. It reminds me of the maps I poured over of Ancient Pompeii when I wrote Fire Mountain for the Rubicon/Scholastic Series Timeline.

The fact is that it allowed Hannah to express a wealth of information about the first scene of Fo's play--that's right: it's only the first scene being represented here and not the whole play. Even the British flag demonstrates an understanding of how Fo intended the play always to be set in the very moment that the play takes place. And that's just one small piece of the brainstorming. You can see at the bottom left hand corner, for instance, that an Oxford English Dictionary makes an appearance to show a definition of farce... You see. Students do still use dictionaries. by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com A Great List for TeachersIf you're interested in comics, graphic novels, and visual narrative in general, and are equally as interested in their implications for classroom teaching, you should certainly consider following as many of the accounts below as you can. These are folks whose tweets frequently focus on the comics industry, comics in K-12 education, or academic scholarship related to comics. A great strategy for those new to Twitter--like educators wanting to learn more about individuals and organizations involved in either comics and education or the wider comics industry--is to follow the people that the folks above are following. After all, they must have a pretty good reason to be doing so! Great Resources for Comics Scholarship

3/27/2014

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com What's Out There...There is considerably more scholarship in the area of visual narrative than most educators or, indeed, most outside the areas of comics publishing and production are aware. Here is a starting point for your investigations. If you find others that you think should be represented here, just let me know and we can add them to the Scholarship tab under Graphica.

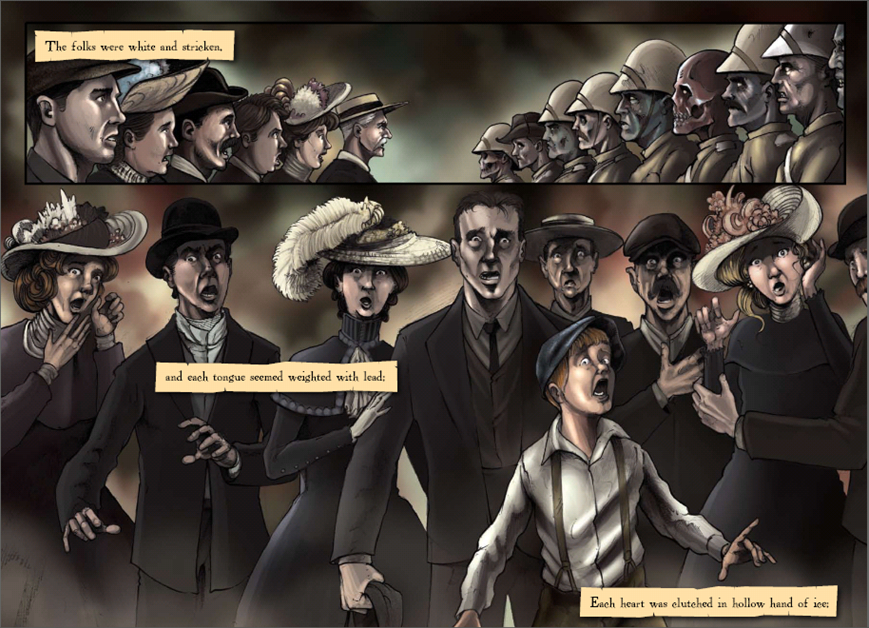

by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com They're Thoughtful, They're Visual, and They're Very Pragmatic[A version of this post was originally published in October, 2013 on a WordPress blog I started. I moved the entire contents of that blog to its present location here. It consisted only of this post. You can also read it on medium.com.] This is not a post about comics or graphic novels per se. This is a post about the future of education that is happening right now. Now don’t get me wrong. I’m interested as much as the next person in the present of education. I’ve been to enough conferences and listened to enough keynote speakers to know that the present is pretty interesting. After all, this is the 21st century, and our classrooms are comprised of an exciting new breed of student: the 21st-century learner. I quite like them, in fact. I can’t help but think, though, that much of what is said about the 21st-century learner, despite being well-intentioned, doesn’t always accord with the needs of the 21st-century learner. Now on the surface it seems to. We talk about how these learners have a different “operating system” than learners once did, and are hardwired to inhabit a visual culture of fleeting images and an aural culture of soon-forgotten soundbites. We’re pretty certain, as well, that they need to complement their "superficial" understanding of a broad range of subjects with deeper investigations of the important few. Talking about these things with one another in the office, discussing them at department meetings, and sharing them at conferences all make us feel like we have a handle on 21st-century education… But this is a post about 22nd-century education. Perhaps more accurately, this is a post about the future of education, and about how much or how little we are doing to prepare for it. I was inspired after much procrastination to post this because of something that happened in my class last term. I learned a fundamental truth about the way in which my students deal with the visual world they inhabit. It reconfirmed my belief that the manner in which students negotiate this world must be an essential component of any secondary school curriculum. I think you will see why in a moment. In preparation for a Grade 11 unit on poetry, I gave my students the image below to consider:  What I wanted them to do is to use their facility with visual images to teach themselves how well they could transfer these investigative skills to the study of poetry. I wanted them to find evidence, use context, interpret clues. And they were fabulous. They noted, for example, that the central figure appeared to be a woman, that her dress seemed turn of the (20th) century or older, that the men in the photo were ministering to her, and that the nooses suggested something ominous was about to happen. Then I decided to push them further. I said that I could only begin the poetry unit once they told me who the woman in the photo was, where the photo was taken, and on what day. I teach in a laptop environment, and I allowed the students to use any technology they had at their disposal. How long do you think it took them to discover her identity? Perhaps more pertinently, how many clicks do you think it took them? If you’re imagining a process of keyword and image searches that quickly narrowed things down, with only a few minutes and a handful of clicks required to answer the questions, then you likely understand something about 21st-century learning. If you’re intrigued, surprised, horrified, or delighted by the fact that the answers can be found in two clicks, however, then read on. It took about 30 seconds before a student got up, walked over to me holding his phone, and read off his litany of responses: “It’s Mary Surratt, sir, And the photo was taken on July 7, 1865 in Washington, DC. She’s about to be hanged for the Lincoln Assassination.” “But…how…?” I asked. I mean, it was only 30 seconds after I set them the task. “Google Goggles, sir. Just took a picture of the image with my phone and the app compared it with the images in the Google Database. Then I just clicked on the link that came up.” That’s right: two clicks. I have a feeling, then, that just as we're beginning to get a handle on 21st-century education, the next century has already begun. Apparently, we needed to begin getting ready for this back in the '50s or something, So although this site will usually focus on the use of comics and graphic novels in the classroom and their wider applications (in visual brainstorming, in recognizing similarities and differences between literary forms, genres, etc.), I still want to hear from educators, students, and parents about where we we need to go in educating today's learners. I want to know how we can transform the real and virtual spaces in which our students learn and break out of the traditional environments we’ve inherited in order to produce the next generation of learners… Well, the next after the next, anyway. by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com The Graphic Canon is a Godsend for TeachersEdited by Russ Kick, the three volumes of The Graphic Canon contain a wealth of wonderful curriculum support materials for teachers. Although there may be colleagues of yours who balk at your desire to use visual narrative in the classroom, they'd be hard-pressed to object to the stunning series of graphic poems, stories, and novel excerpts that constitute these three volumes. Your fellow department members only want to teach "The Canon?" That's fine. With The Graphic Canon they can do just that!

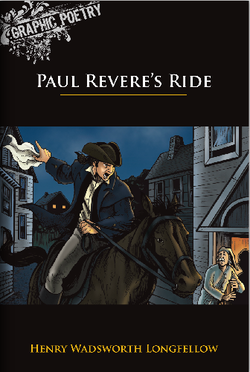

I could talk at great length about this series of books, and no doubt in future postings I'll be looking at how to use them in the classroom, but for now your best resource on the series is their WordPress site. I can tell you that each volume in the series covers a distinct period of time and the literature that goes with it. The first volume's selections range from the Epic of Gilgamesh to Shakespeare to Dangerous Liaisons. Volume 2 takes readers from Coleridge's "Kubla Khan" to the works of the Bronte Sisters and finally to Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray. Finally, the third text goes from Conrad's Heart of Darkness to Hemmingway to Infinite Jest. From my perspective, the series is of most use to high school educators who either want to...

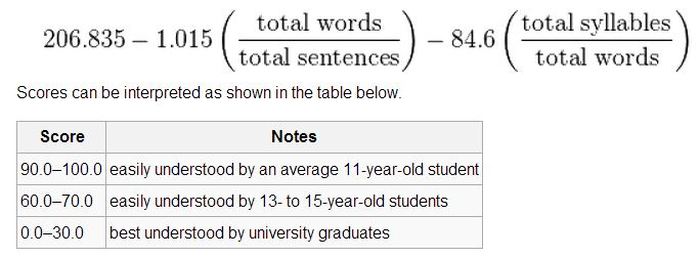

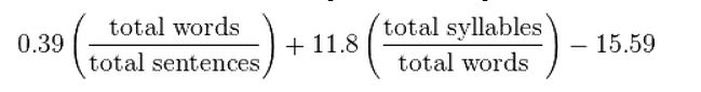

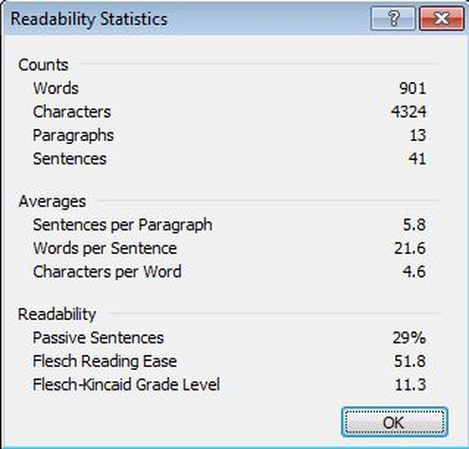

Of course, there is nothing preventing the teacher from constructing an entire unit around these selections. With younger students, however, you might not have enough selections that are geared towards a junior or middle school audience, so that a series like Graphic Poetry from Rubicon/Scholastic would be a better option. Scott Robins @Scout101 also mentioned in a Tweet the Visions in Poetry series from @KidsCanPress. by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com Having Students Take Notes in Their Own Way is the KeyIn a couple of previous posts, I showed you examples of Grade 12 students doing a comparative analysis of Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire using a Visual Brainstorming technique that saw them employ a combination of words, images and symbols to represent their thinking. Although the examples I showed featured students with excellent artistic skills, it's important to remember that Visual Brainstorming and Visual Note-Taking are not simply exercises in illustration. They are exercises in brain-dumping. Think of the activity as less about drawing and more about freewriting, but with some license to use the visual and without the need to avoid lifting the pen from the page. Here, Kailey has amassed an excellent amount of information about the opening scene of Dario Fo's Accidental Death of an Anarchist. Her only direction was to think about a few basic concepts: character development, staging, humour, and dialogue. She was also encouraged to ask questions right on the paper about things that were happening in the scene that she might not fully understand. The results are so staggering that I'll likely be transferring this to the exemplars section of the website so that I can generate a slightly larger illustration to show you what she came up with. Please try these exercises with your students! You may be quite pleasantly surprised not just with their artistic skills, but by how much knowledge and understanding they are able to articulate when given the freedom to express their ideas in this manner. by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com The Flesch-Kincaid Scoring SystemI was thinking the other day about whether those who write comics and graphic novels for the trade market consider the demographics of their intended audience--not in terms of the appropriateness of the content of what they are writing, but in terms of the language they are using. Often when teachers want to use a graphic novel that was not specifically designed for the classroom--like Persepolis, Maus, or Watchmen--they are not initially sure whether their students will be able to make sense of it (i.e. whether it's of an appropriate grade level for their students in terms of the issues it address or its use of language). This got me thinking about whether there would be a good resource to talk about in this blog that all teachers and all writers should consider using when respectively teaching and writing. Fortunately, there is, and the resource is closer than you think! It's called the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Test and it's what every educational publisher knows when putting together any kind of book for the classroom, including leveled comics and graphic novels. What the test amounts to is a pair of equations that can analyze both the readability of a given text and its associated grade level. Here are the snippets courtesy of the one website I could find with a very readable presentation of the two tests: Wikipedia! Reading Ease TestGrade Level TestWhat are the implications for teachers and writers? Well, those writing in any genre can check the basic readability of the physical language structures in their prose by using the Proofing tab under Options in Microsoft Word. The hyperlink above takes you to Microsoft's site. The reason very few people use this function, however, is that it is defaulted to "off" in Word. You need to check a box called "Check Readability Statistics" in order to turn it on. Then you'll be able to see something like this: when you spell check a document. If you write comics or graphic novels, it's a bit more challenging to use the feature. You have to include on a Word page just your dialogue. Otherwise, the reading will be skewed. It's an especially valuable tool for those who want to write for the educational publishing industry, though, since it can ensure that the physical structure of the writer's prose is not way over the heads of the intended audience. In the above example, it is indicating that a student in Grade 11 lshould be able to understand the document on a first reading. Numbers over 12 indicate that a student would generally need to have a postsecondary education to ensure their understanding of the language structures.

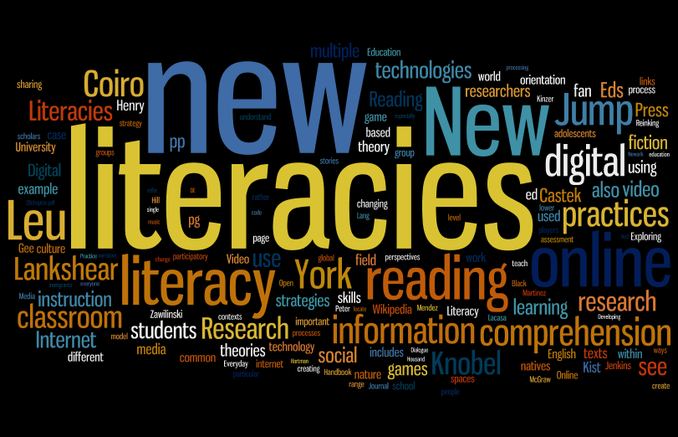

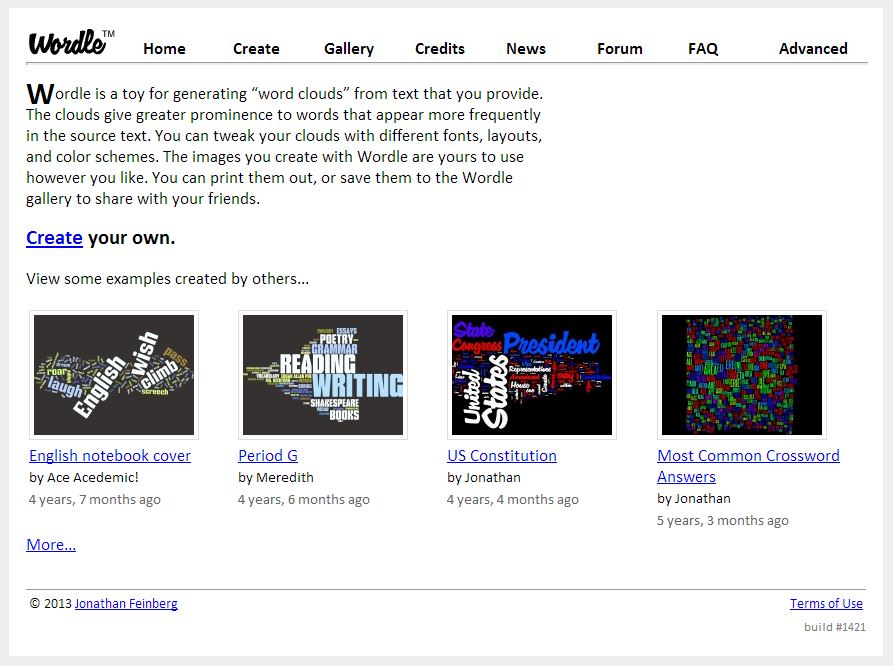

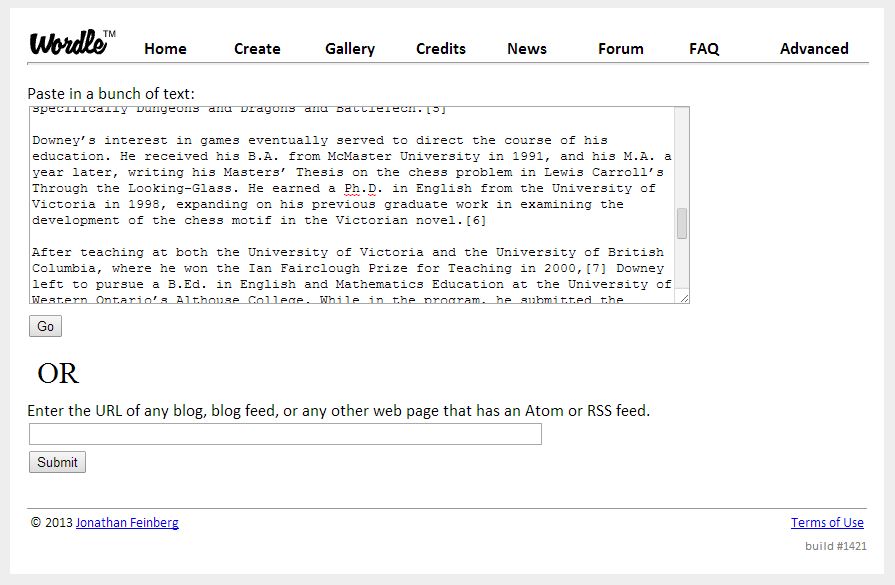

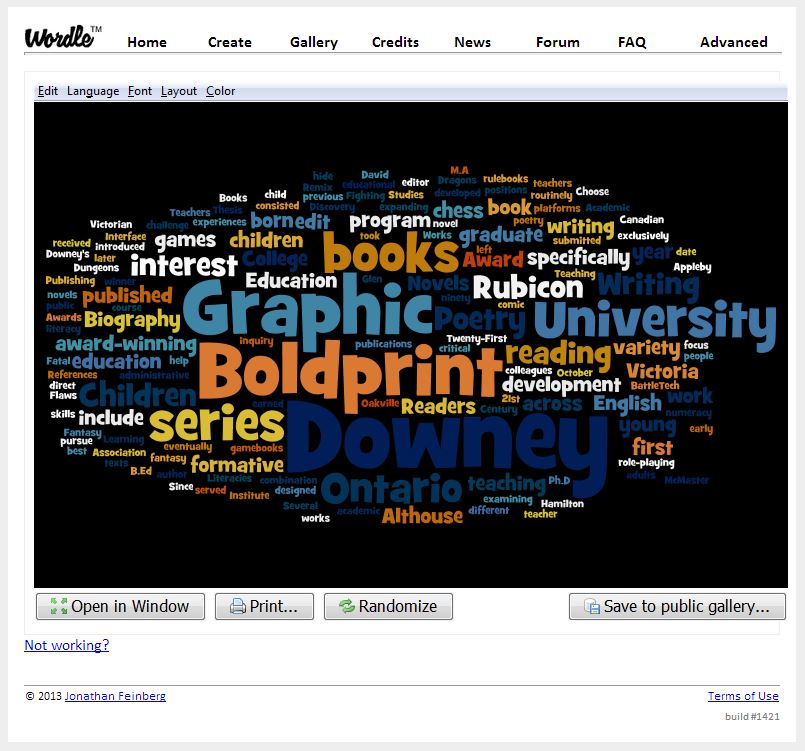

For teachers, there are very practical uses for this. Have your students check the grade level of their writing. Are they in Grade 12, but the Flesch-Kincaid readability test is saying that the student is writing at a Grade 4 level? It might be the case that there is a lot of dialogue in the student's text--which tends to generate lower scores--or that the student uses a number of short, monosyllabic sentences. Is your student in Grade 4 and writing at a Grade 12 level. It might be that they are constructing run-on after run-on and aren't sure where to put the period! Okay, now I've shown you the resource. See if it can work for you! by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com  Tag Clouds Are Powerful Learning Tools that Draw upon the Power of the Visual!One thing that comics taught me was the power of a visual medium to tell me something that I needed to know about a story, its plot, its characters, and how to make meaning of a narrative. It also got me thinking that other visual devices must be similarly effective, even when applied to other kinds of texts. I had also always been fascinated by Discourse Analysis, a branch of literary and textual studies that examines how discourse unfolds in everything from a series of comic books to a website devoted to spoiler updates about that series of comic books! At www.wordle.net, however, you can find an immensely powerful visual tool. Now if you've worked in education you've seen these over and over again. No doubt your state or provincial governing bodies for education have distributed materials containing tag clouds like the one above that contain key terms. In these clouds, words that appear more frequently are larger in size. As it turns out, though, there is significant application in the English classroom for these. Here's something you can try (actually, you should have your students do this as a regular habit): 1. Prior to submitting an essay or writing assignment, have students cut and paste the assignment into a Wordle. The students go to www.wordle.net (they can also use the website Tagxedo, but Wordle is quick and effective). The student cuts and pastes their writing by clicking on the Create tab. 2. Once you hit "Go," Wordle will take the student's text and create a word or tag cloud out of it. By looking closely at the Wordle, a student can glean a lot of information! So What Is This Important Information?Before we get to that, make sure that the student goes to the Language tab and clicks on "Remove Common English Words" so that it is unchecked. This will allow the student to see all of the words in the Wordle. Now get the student to find the important information about his or her writing below:

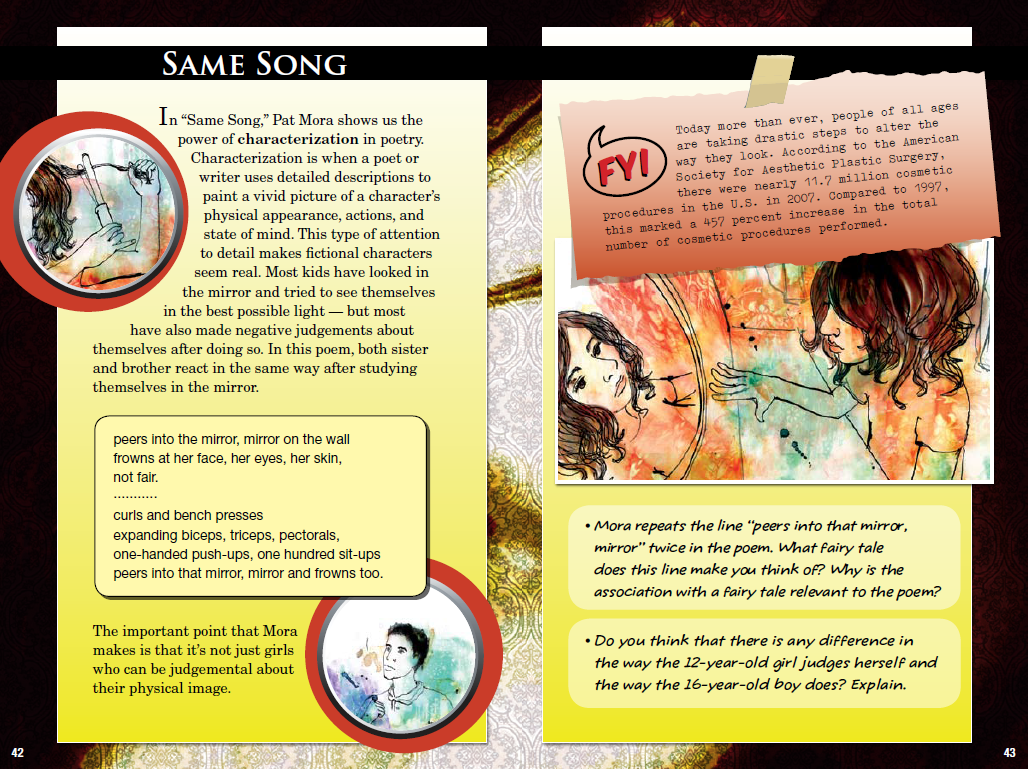

Try this great visual activity with your students and let me know how it goes. Watch, too, to see if some of the "language" of talking about Wordles begins to rub off on how they talk to one another about their writing during peer editing and revision sessions (e.g. "I notice in your Wordle that you use the words `due' and `fact' a lot; you might be saying `due to the fact that' too much and should replace it with `because'"). In my experience of using this activity, I find that their language will start to change a bit! by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com An Award-Winning Series that Presents Contemporary and Classic Poems in a Graphic Format The Graphic Poetry series by Rubicon/Scholastic is one that is near and dear to my heart. As you'll recall from my earlier blog post on "The Literary Features of Graphic Novels," I served as series editor, having proposed a couple of panel pages for it and provided a rationale to the folks at Rubicon. What makes the series work is that it uses a highly visual format of presenting poetry to a roughly middle school audience (although it can be used with younger or older students). However, the poems read just as they would in a text-only format because there are no extraneous sound effects or narrative asides. Sometimes the text of the poem is in narrative caption boxes and sometimes it comes out of the mouths of the characters, but it is uninterrupted by material that is not a part of the poem proper. Each book contains one or two poems and there are twenty- one titles in all. Each also contains the poet biography's in a Between the Lines section that additionally focuses on developing children's familiarity with a specific literary feature or trope. The series won the 2010 Textbook Excellence Award from The Text and Academic Authors Association and the 2011 Teachers' Choice Award for Children's books from Learning Magazine. For more information on the series and to look at how it can be used in the classroom, visit www.graphicpoetrybooks.com and then click the link for Canada or the US. As well, there is a PDF resource on the site, Teaching Graphic Poetry, that you can download and use in your classes! by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com Activities Inspired by the Visual Can Yield Amazing ResultsThis one I just had to share with you. In the lead up to teaching Persepolis this year, I wanted to give my students as many opportunities as possible of working with the visual. If you read my blog post about the "Cave Art" activity, you'll recall that it required students to depict a day in their life, a challenging encounter, or their best moment on the planet, etc. as a cave art montage. In effect, the Cave Art activity is a kind of visual brainstorming about a moment in the student's own life. The above collage by Marwa is fantastic, looking like it sprang to life out of the Futurist movement in Western art. There's a very cool variation on this activity that I alluded to last time. It has the following steps:

What are some neat results?Perhaps the coolest thing about the activity is that regardless of whether they feel their collage does or does not represent them, the students are really only tasked with making a judgment and defending it. It's not a failure if it doesn't represent them nor is it an overwhelming success if it does. However, when I did this with my students this year there were some unexpected insights that resulted, one of which came from a student who suggested that although his collage didn't represent him, what did was the process he went through to put it together. These are the kinds of insights we want from our students. As a side note, I did my own collage to see what I would come up with. The result is below: As this site grows and develops, I guess you'll be the best judge as to whether or not this represents me. It's just crazy enough that it might... by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONSHere are some common questions that come up about teaching comics and graphic novels in the classroom. If you have any others, please send them our way through the Contact tab and we'll add them to the list! Question 1 -- Why would I use comics and graphic novels in the K-12 classroom? There are a variety of reasons for using comics and graphic novels. I talk about these issues at length in a pair of opinion pieces I wrote for the Sequart Research and Literacy Organization: Everything I Know I Learned from Comics and Comics in the Classroom. Comics and graphic novels are ideal for reluctant and struggling readers because marrying the verbal and the visual helps to engage them while building their vocabulary and comprehension. However, the genre is also a must for the academic classroom because visual narrative is a significantly underrated kind of text that has tremendous interdisciplinary applications. Question 2 -- How do I know what comics or graphic novels to use? I've been asked this question so much by educators that it motivated me to develop this website. The straightforward answer is that you have to do your research, but so much is being written now that the searching is becoming easier. Starting with comics and graphic novels designed specifically for the classroom by educational publishers like Oxford and Scholastic is a great idea, and using this site to get a sense of what's out there in the trade market that can be used in the classroom is the next step toward more fully integrating visual narrative into your curriculum. Question 3 -- How do I talk to parents who complain that their kids should be reading the classics, not comics and graphic novels? Kids should be reading the classics, but they should also be reading widely and broadly across a variety of genres. Doing anything less than this ignores important forms of writing that are essential to a 21st-century learner's growth and development. Parents are often not looking to cast aspersions, but simply to be reassured that the books their kids are reading will help them in some way. Question 4 -- I didn't grow up reading comics or graphic novels, so I'm not sure I'd be comfortable teaching them. How do I learn more? You're at a good starting point with this site. Explore it and then have a look at the wealth of information that this site links to. It's the product of dozens of hours of painstaking research, so feel confident that what you need to know is out there and that Comics in Education is helping you to find it. Question 5 -- Is Comics in Education available for in-class service or professional development support? Our mission is to advance the use of comics and graphic novels in the K-12 classroom, and Comics in Education is always available to work with teachers, students, parents, administrators and library professionals to that end. Please contact Comics in Education through the Contact tab above for rates and availability in your area. by Glen Downey, Comics in Education, www.comicsineducation.com Filmic language allows us to talk about key elements of the visual in graphic storytelling. However, it is useful to draw upon critical, theoretical approaches like "The Gaze" that allow us to talk with greater sophistication and insight about what is happening in a visual narrative. Gaze theory is a theory about how men and women look at one another and what the implications of this looking are in visual culture. The theory examines subject/object relations and sexual politics, but of special interest to us are its insights into how visual media is composed. Attention |

| Although we sometimes think of New Treasure Island (1947) as the first manga comic, Osamu Tezuka's The Mysterious Underground Men is the one that the author himself considered the first of his "story manga." It tells the tale of Mimio the Rabbit who tries desperately to prove his humanity while helping his friends deal with mysterious creatures under the earth dead set on taking over the surface world. The work is amusing, exciting, and, in the final analysis, heartbreaking, serving to shape with its ending the course of manga in the nearly 70 years since its publication. |

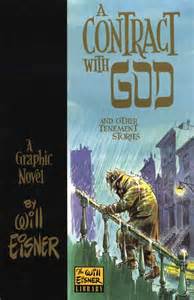

A Contract with God (1978), by Will Eisner

| Generally considered to be the first graphic novel in the North American tradition, this 1978 classic by Will Eisner showed a generation of readers something that they had forgotten: that it did not simply have to be the Sunday funnies or feature an assortment of costumed crusaders. Eisner sets his collection of stories on the fictional DropsieAvenue in the Bronx, and what he achieves in telling stories of the very real human dramas that unfold every day on our city streets--stories of triumph and of tragedy--changed the course of comics history. In some ways, A Contract with God is peerless in the canon of visual narrative, and is a must read for anyone undertaking a serious study of the genre. |

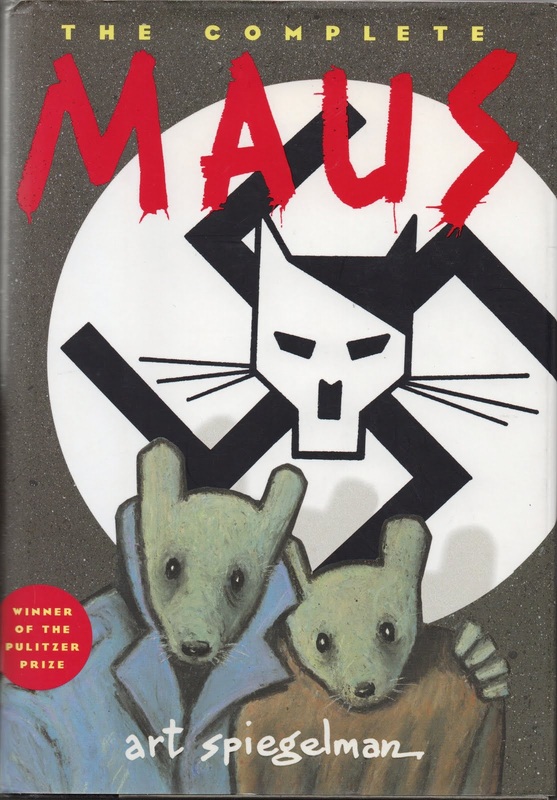

Maus (1986), by Art Spiegelman

| If you are an educator who has taught a full-length graphic novel in your middle or high school English classroom, the overwhelming chances are that you taught Art Spiegelman's Maus. Telling the story of Spiegelman's father as a Holocaust survivor during the war, the novel uses the ingenious and sometimes controversial device of anthropomorphized animals. The story is not only about the horrifying experiences of Spiegelman's father, however, but about the relationship between father and son that develops over the course of the novel, and the latter's efforts to tell his father's story as a visual narrative. |

The Dark Knight Returns (1986), by Frank Miller

| Few would argue that The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller is the single most important Batman story ever told. It is ten years after an aging Batman has retired that the crime and violence on the streets of Gotham are in desperate need of his glorious return. With Carrie Kelly, a female Robin at his side, Batman must work to defeat rival mutant street gangs, face off against two of his greatest foes--the Joker and Two-Face--and then go up against his longtime ally, Superman, in a battle that only one of them can survive. The Dark Knight Returns is often seen as being almost singlehandedly responsible for the resurgence of interest in Batman and for the film franchise that followed. |

Watchmen (1986), by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

| One can't underestimate the importance of Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. A decade ago, Time Magazine compiled a list of the Best 100 novels from 1923 to the present, and Watchmen was on it. Powerful, compelling, and complete with characters who burn into the retina of our collective memory, this graphic novel simply must be read by any student of the genre. Chronicling the fall from grace of aging superheroes, this Hugo-Award winning graphic novel is one of the most frequently studied works of visual narrative in the postsecondary academy. It also underscores the profound contribution to the genre by creative genius, Alan Moore. |

Finder (1996-present), by Carla Speed McNeil

| With her webcomic Finder, Carla Speed McNeil introduced us to the remarkable world of her wandering protagonist, Jaeger. In the first volume of the series, Jaeger becomes involved with a family trying desperately to recover after escaping a psychologically abusive father. Although McNeil chooses a science fiction setting for her series, her characters are all too human in their depth and complexity, and the series itself explores important issues about family, identity, and the self. The series has garnered no small amount of critical praise across the various volumes that have been published in web and print form over the course of the last two decades. Finder is, when all is said and done, a superlative achievement. |

Transmetropolitan, Volume 1 (1997), by Warren Ellis and Darcik Robertson

| The brainchild of the irrepressible Warren Ellis, Transmetropoltian, Volume 1: Back on the Street tells the story of Spider Jerusalem, an investigative reporter living in the 23rd century who returns from his self-imposed exile to a civilization whose corruption and degradation drove him away in the first place. Now, as a reporter for The Word, Jerusalem sees it as his mission to confront the injustices of his society in the way only he can. As a post cyberpunk comic, Transmetropolitan speaks volumes about how Ellis sees our ultimate salvation not in the hands of costumed heroes with superhuman powers, but resting with the common man willing to stand against the forces of corruption. |

Persepolis (2004), by Marjane Satrapi

| Educators who have taught a graphic novel at the high school level that was not Art Spiegelman's Maus have likely taught Persepolis, the compelling graphic narrative by Marjane Satrapi that chronicles her life in Iran at the time of the 1979 revolution. With her we see the revolution through the eyes of a child who must very quickly grow up, confronted as she is with the terrifying events that shaped the country she loved so much. What is so profound in Persepolis, however, are the important things it has to say about family, and about how it can be the only thing to hold onto when the rest of the world is going crazy. Satrapi's use of the symbolic is an especial strength of the narrative, as is her understanding of the limitless potential of the visual in telling such a story. |

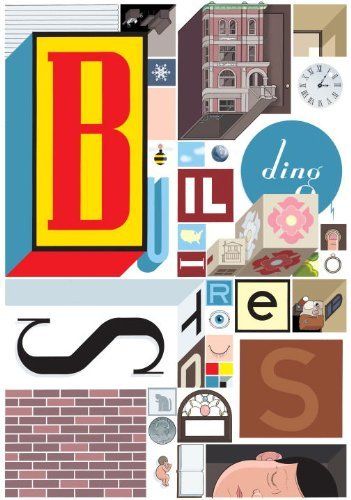

Building Stories (2012), by Chris Ware

| Hands down the best graphic novel of 2012 and arguably the best novel of 2012, Chris Ware's Building Stories is in some ways difficult to fathom. Developed and written over the course of ten years, the novel is comprised of a series of fourteen differently formatted, sized, and bound pieces that tell an interconnected series of stories from a Chicago three-flat occupied by a curious cast of characters. Building Stories garnered four Eisner awards on its own and was on the Top 10 book lists of most major reviews, including the New York Times, Time Magazine and Publishers Weekly. |

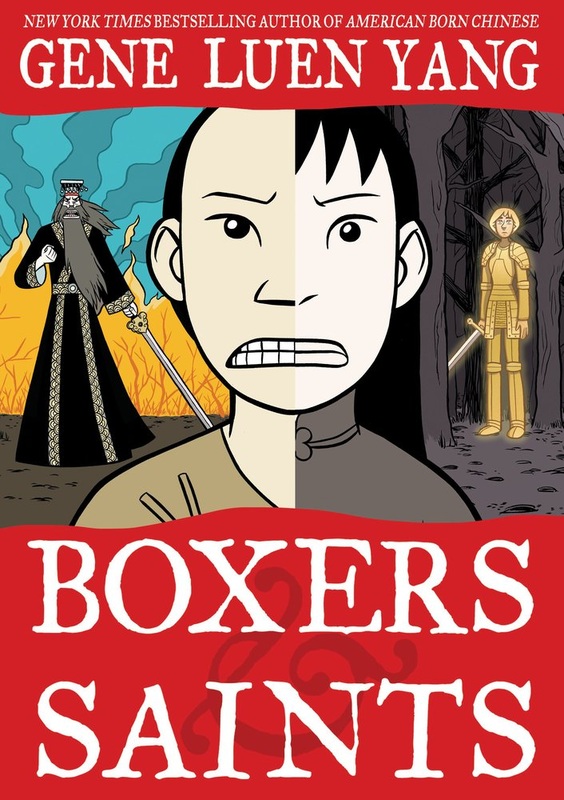

Boxers & Saints (2013), by Gene Luen Yang

| Many had Boxers & Saints on their list of the Best Graphic Novels of 2013 and with good reason. This pair of graphic novels tells the story of the Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the 20th century. Told from the perspective of a young person on either side of the conflict, it shows the world the immense talent of Yang, who previously impressed with American Born Chinese. In Boxers, Little Bao, a Chinese peasant boy, grows up to lead his people against the Christian influences that he sees as threatening his homeland. In Saints, Vibiana must decide whether to remain true to her Christian faith or abandon it in favour of rebellion. |

Use Visual Note-Taking Strategies for Better Results!

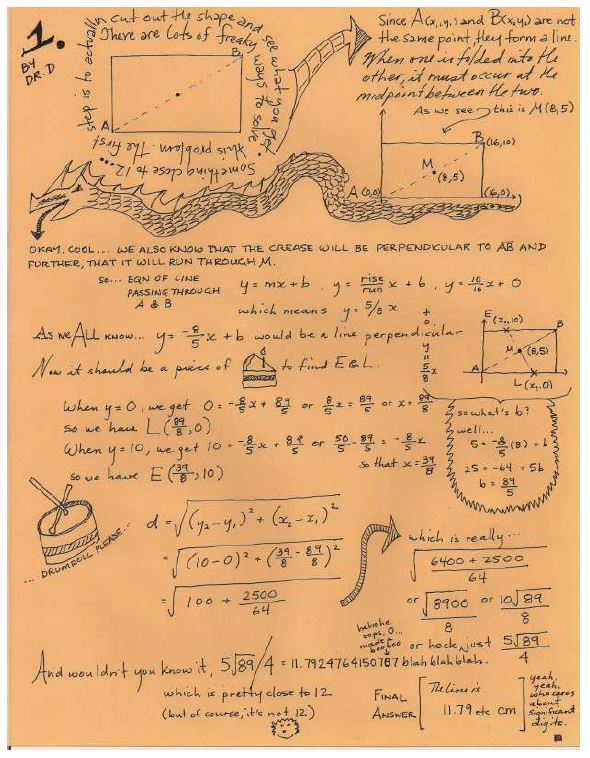

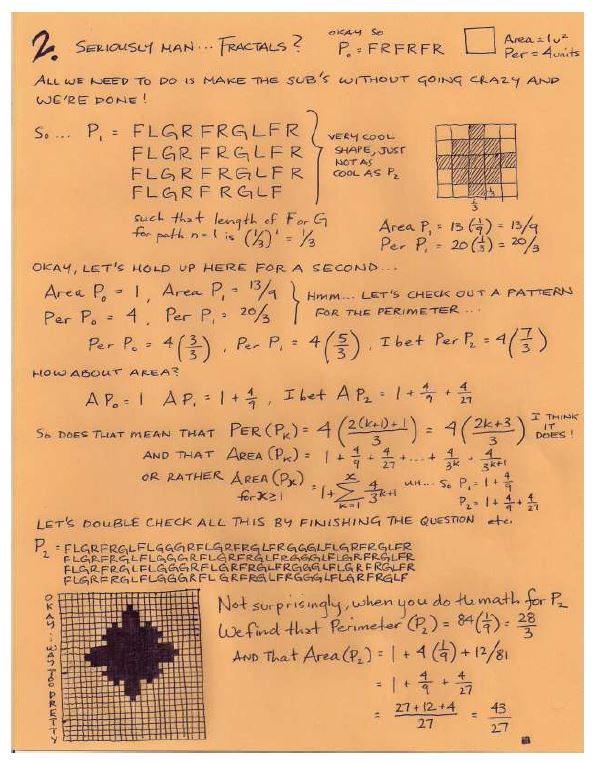

I know in the mathematics classroom that we're ever-more conscious about allowing students to find their way to the answers to problems. Gone, I hope, are the days of forcing students to take a single road along their journey through our mathematics curriculum.

I was never big on taking that road myself. When asked to solve a math problem, I always wanted the solution to look cool for some reason. I think this had to do with my formative reading experiences being so tied to comics, detective fiction, adventure stories, and the manuals and gamebooks of fantasy role-playing games. I wanted the journey to be exciting!

A few years back, I was teaching at a school that held a math contest for students and faculty. I found the questions really challenging, and that's with ten undergraduate math courses under my belt!

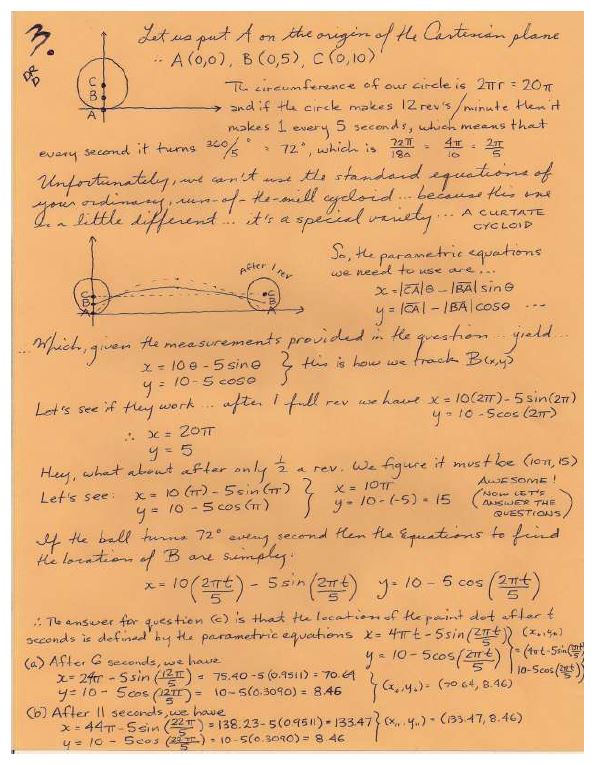

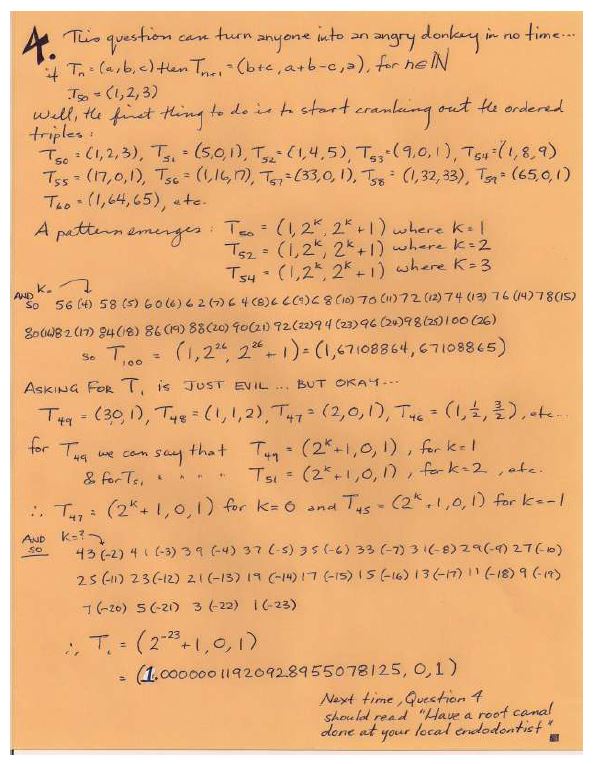

I managed to win the contest (which I think my colleagues found strange given that I taught in the English department), but the way I answered the questions had something to do with it: Here were my responses, and I apologize in advance for having no longer any clue what the questions were...

I was never big on taking that road myself. When asked to solve a math problem, I always wanted the solution to look cool for some reason. I think this had to do with my formative reading experiences being so tied to comics, detective fiction, adventure stories, and the manuals and gamebooks of fantasy role-playing games. I wanted the journey to be exciting!

A few years back, I was teaching at a school that held a math contest for students and faculty. I found the questions really challenging, and that's with ten undergraduate math courses under my belt!

I managed to win the contest (which I think my colleagues found strange given that I taught in the English department), but the way I answered the questions had something to do with it: Here were my responses, and I apologize in advance for having no longer any clue what the questions were...

Q1. Killer Geometry Question

Q2. Fractals -- It was brutal

Q3. Hypocycloid Question (I nearly died)

Q4. I honestly don't even remember this one...

I think when we allow our students to draw their math answers, write out their frustrations about their math answers, and use visual brainstorming techniques for their math answers, we're giving them opportunities to arrive at these answers in very useful ways. If you encourage visual brainstorming or having kids use doodling in their written responses to questions, send along some examples because we'd love to feature them at Comics in Education!

Glen Downey

Dr. Glen Downey is an award-winning children's author, educator, and academic from Oakville, Ontario. He works as a children's writer for Rubicon Publishing, a reviewer for PW Comics World, an editor for the Sequart Organization, and serves as the Chair of English and Drama at The York School in Toronto.

If you've found this site useful and would like to donate to Comics in Education, we'd really appreciate the support!

Archives

February 2019

September 2018

June 2018

March 2018

April 2017

November 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

September 2015

August 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed