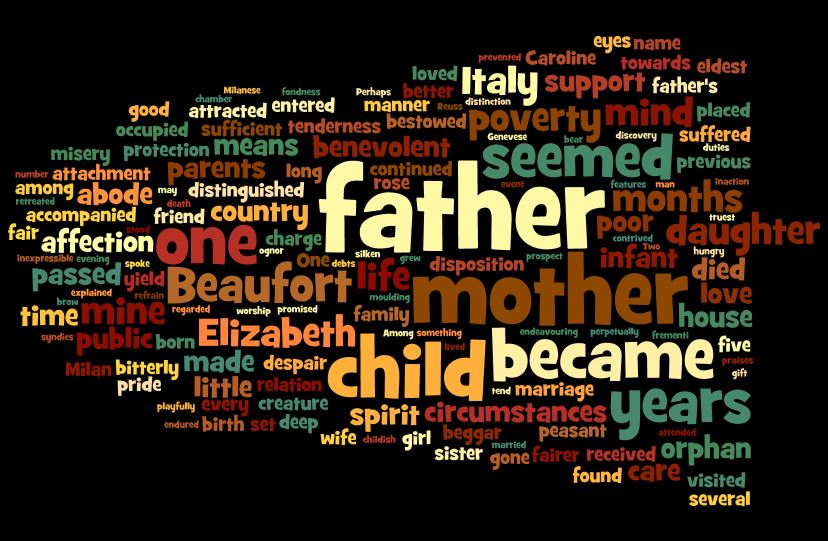

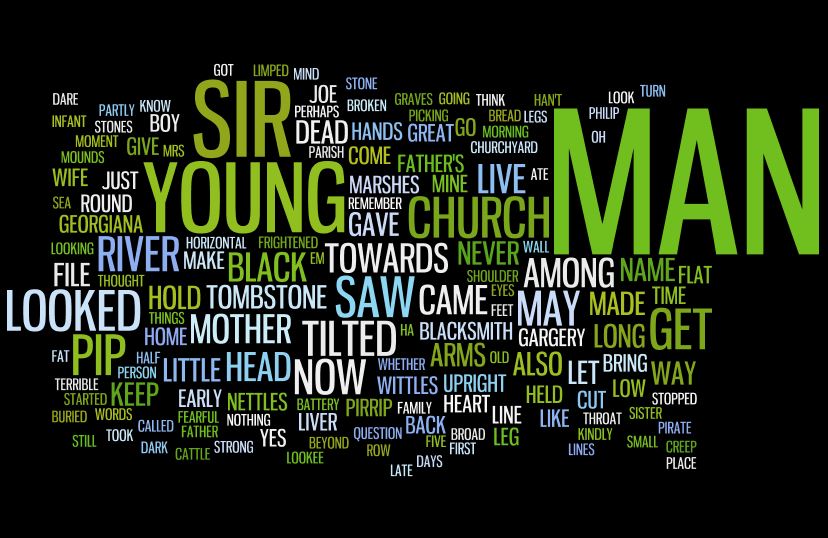

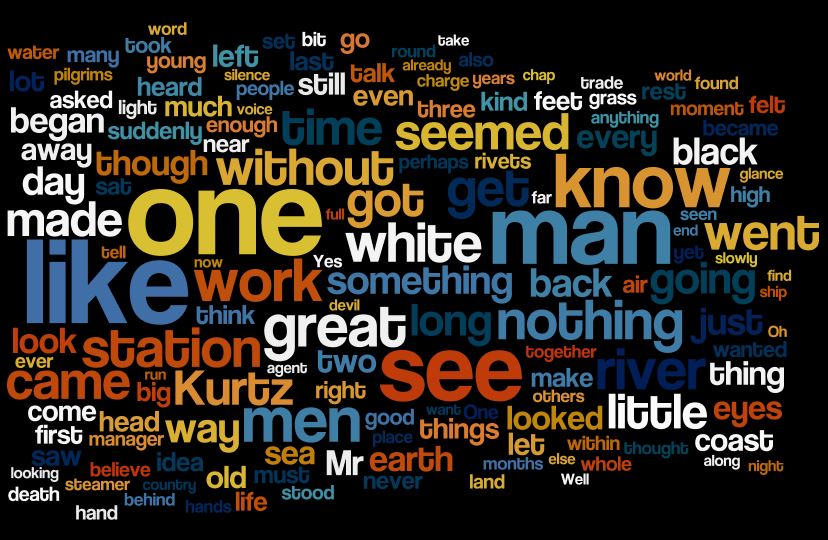

At Comics in Education, we conceptualize visual narrative as a broader category than what we think of as traditional comics and graphic novels. Its implications and applications for the K-12 classroom are likewise also broader. Take, for instance, the three novels below whose first chapters are rendered as Wordles. It turns out that these tag clouds can generate some exciting activities: Novel #1, Chapter 1Novel #2, Chapter 1Novel #3, Chapter 1 Think about the great thinking and problem-solving activities that students can engage in with these Wordles. They can be used as a pre-reading activity in getting students to consider what the works they are about to study might deal with. Consider the following:

You can see that activities during and after reading also suggest themselves, and that analyzing the word distributions here can be a fantastic springboard into a fuller investigation of the styles of the three authors. No doubt, some of you are yelling at your laptop or handheld and calling out the names of the novels as you read this. If that's you, then Tweet your answers to me @teachingcomics or @GlenDowney. The first person to get all three correct will be immortalized for their victory in this very blog post! If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy:

0 Comments

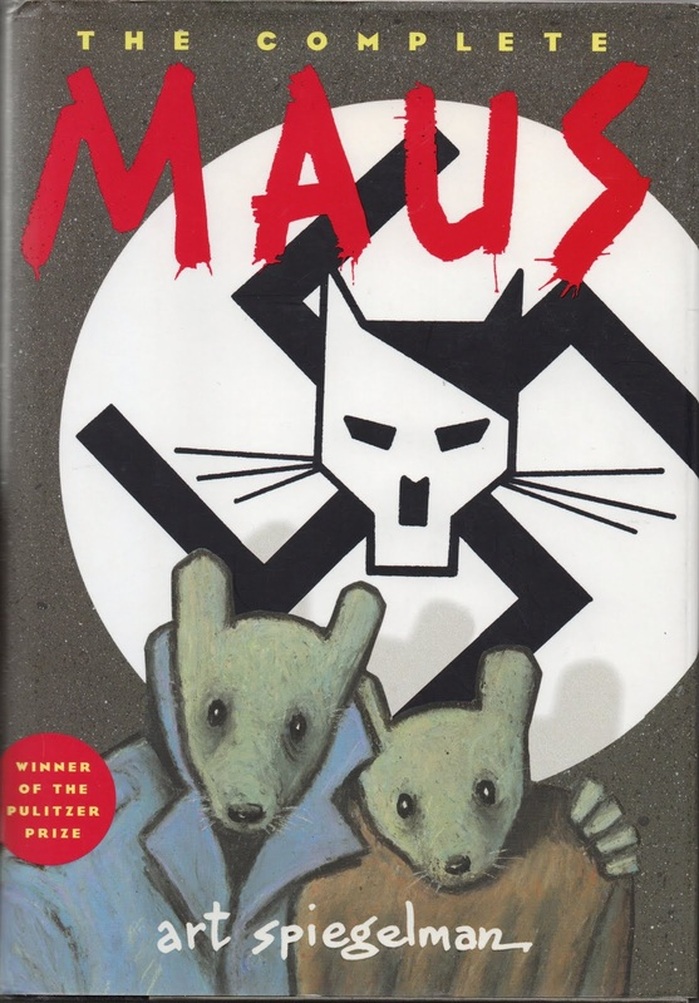

Every once in a while I have my students participate in an experiential activity whose purpose is to teach them just how much information contemporary technologies provide them access to. In the activity, students must put away their laptops and smartphones, and then use nothing more than the technologies that existed in the early 1980s to answer a series of very challenging questions. They are permitted to use the school library, and can look up books on the library's computer (given the absence of a card catalogue) but they certainly cannot surf the web, use keyword searches, or do anything that would allow them to answer the questions in the nanoseconds it would take them with technology. On one occasion, a student came up to me who was trying to figure out what a particular word in one of the questions meant. "Can you tell me what this word means?" the student asked, to which I replied, in teacherly fashion: "Where would you find the definition?" The student looked at me puzzled, then looked at the question again, but doing so didn't seem to help. "I don't get what you mean," he said. "Wouldn't you use a dictionary?" I replied, after a short pause, giving him that look that suggested I was trying to break something gently to him so that he wouldn't feel altogether too silly. But what he said next was a stunner. "Uh...how am I supposed to do that? You took away our laptops..." Before the bibliophiles out there begin to lose their minds over this, let me take a moment to say that the kid was right. It's likely that he had never looked up anything in a print dictionary, and who can blame him? Dictionary and encyclopedia publishers have largely moved to online platforms now, and I can get dozens of definitions for a single term, cross-indexed, hyperlinked, and all in the time it takes me to type in the word. The problem, however, is that many writers and thinkers in the past two decades have used stories like the one above to write articles about the "Death of the Book," suggesting that digital technologies have changed the publishing landscape forever and that it's only a matter of time before books are entirely obsolete. Inevitably, this prompts others to write about how the book can't die or about how the news of its impending death is an exaggeration of the facts. The problem, as I see it, is that when people write about the "Death of the Book," they're beginning the conversation by talking in metaphors. Framing the discussion in this way isn't really productive, however. People have strong feelings about reading, and about the relationship they have with books, and so it's no surprise that they decry what they see as the end of a beautiful friendship. The whole argument, however, is silly. Should we really be worried that the advent of electronic libraries, the decline of traditional bookstores, and the changing reading habits of young people are threatening to destroy printed books? No. Why shouldn't be worried? Well, we went from carving things on stones to writing by hand to printing out manuscripts, to housing them digitally, and in the process we seemed to increase the number of people who can read and who enjoy it. And it's simply not going to be the case that we discover new ways of reading that are awful or terrible or that people won't like, because someone will simply come up with something that isn't awful and isn't terrible and that we do like. I grew up loving books and going to libraries and bookstores. I loved leafing through dictionaries and encyclopedias to discover new things. And I especially loved the smell of walking into my local comic book shop and seeing the titles, old and new, lining the shelves. And although I still love books and feel a sense of nostalgia about my childhood reading experiences, I'm not going to pen an elegy about the death of the book. They are changing and transforming and gradually becoming something new and different, but when all is said and done, they are just the medium through which we get to learn about other people's stories. And it's not like we're going to stop telling each other stories any time soon. If you enjoyed this article, or even if you didn't, don't worry. Perhaps the book will make a resurgence some day, as shown below: Even if you're teaching Maus for the first time, there are more resources out there than you might think...It can be both an exciting and daunting task for teachers if they're teaching a graphic novel for the first time, and that graphic novel happens to be Art Spiegelman's Maus. Although it is one of the most frequently taught GNs in the high school classroom (along with Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis), there are dozens of resources available to assist you in your preparations. Here are some good ones to get you started with your unit!

These resources should help you to prepare a unit that your students will thoroughly enjoy. If you still have any questions about teaching Maus, don't hesitate to ask us here at Comics in Education! If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

Don't underestimate the appeal to visual learners If you're not up to the challenge of ordering Oxford's graphic novel versions of Macbeth or Romeo and Juliet for fear of your colleagues' admonishing stares, consider the wealth of YouTube clips from Shakespeare, the Animated Tales. This series covers some of the most beloved of Shakespeare's plays and is an excellent way to help students improve their understanding of the Bard and his work. The series ran on BBC 2 from 1992 to 1994 and consists of twelve half-hour long programs. The series even inspired the Shakespeare Schools Festival, an annual event in which students perform half-hour long versions of Shakespeare's plays. If you're interested in the series, it can be ordered online. Here are the plays that are featured: SERIES 1

SERIES 2

What younger students will enjoy about the series are the different approaches to animation in each of the videos--approaches that attempt to match well with the play in question (you can see this just by looking at the still frames above). And heck, whose to say that some of our older students couldn't benefit from having a look at Shakespeare, the Animated Tales? If you enjoyed this video, you might also enjoy:

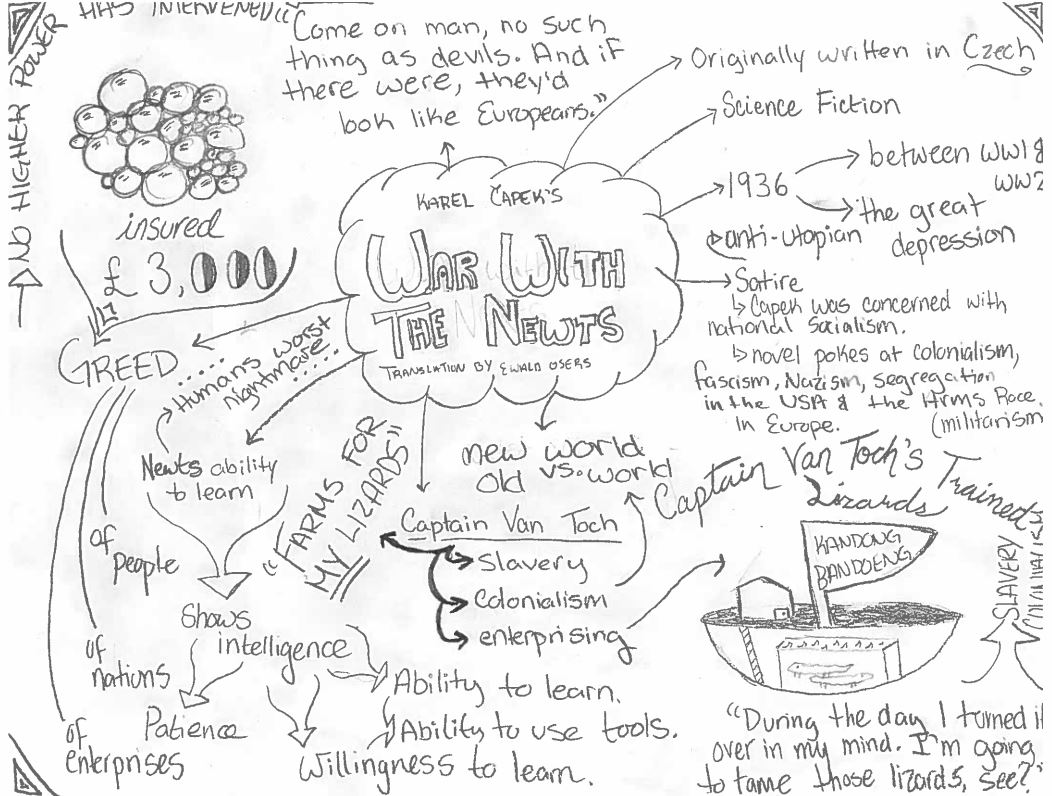

A Visual Intro to Sci-Fi and Satire: Adding War with the Newts to Your High School Reading List

5/20/2014

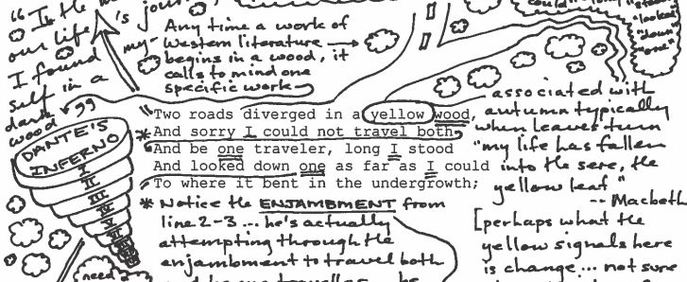

A nice way to acquaint your students with a new text they'll be studying is to use something visual. It's especially powerful if this visual piece is done by a former student who has studied the work. We've all used video clips and the like to kickstart a unit on Shakespeare, so why not use a piece of visual brainstorming to do likewise. As we can see in the example above from Hannah, such a piece doesn't take a long time to create and it can capture some of the essential learnings and enduring understandings that are takeaways from the unit. Hannah's example deals with Karel Capek's War with the Newts, a science fiction novel written in the 1930s that satirizes the rise of Fascism, Nazism, as well as racism in America. In the story, a race of sentient newts is discovered, and through a series of circumstances paralleling the events following the end of WW1, the Newts eventually rise to a position of power. A great pre-reading strategy is to give students a piece of visual brainstorming like this and to ask them what they think the novel will be about. This can be done in combination with showing them the short video clip below. The result is that students are required to activate their prior knowledge and make predictions prior to reading, which are both excellent strategies to better ensure that they eventually grasp the enduring understandings of the unit. Try it with your students and let me know how it goes! If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

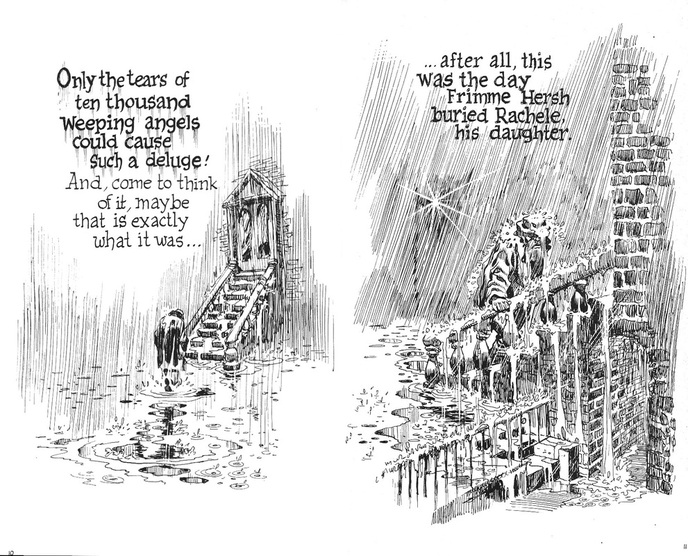

Why having some (etymological) perspective is a good thing... A subject that rears its head from time to time in the world of comics has a fair bit to do with the story depicted above. It's from Will Eisner's A Contract from God, of course, a work that has commonly been regarded as the first modern graphic novel. The latter term, however, has often ruffled the feathers of those who write comics, since it strikes some as pretentious--as a term that tries to turn comics into something more than what they are. But let's face it: the argument has never really been about the term "graphic novel." Rather, it's been about the term "comics." As pretentious as "graphic novel" might seem to some, the term "comics" only occasionally identifies what's actually happening in a comic book. The word "comics" is simply convention; it came into existence in the late 19th century and we've collectively kept it in use. You'll hardly be surprised to discover that "comics" derives from "comic," and that the latter is the adjective we get from the noun "comedy." However "comedy" itself has an interesting etymology, as we see from Douglas Harper's Online Etymological Dictionary: comedy (n.) late 14c., from Old French comedie (14c., "a poem," not in the theatrical sense), from Latin comoedia, from Greek komoidia "a comedy, amusing spectacle," probably from komodios "actor or singer in the revels," from komos "revel, carousal, merry-making, festival," + aoidos "singer, poet," from aeidein "to sing," related to oide (see ode). If we put aside books whose authors would refer to them "graphic novels" and just focus on traditional, mainstream comics, is the term "comics" particularly useful in describing such works? Would you say that there is typically more of the comic than of the dramatic or tragic in a typical issue of The Avengers? or Batman? or apparently July's issue of Life with Archie for that matter? Instead of getting bent out of shape about the multiplicity of terms with which we refer to comics, we should probably just embrace them. If you happen to think a work is pretentious because its author refers to it as a "graphic novel," think carefully about what is really bugging you. If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

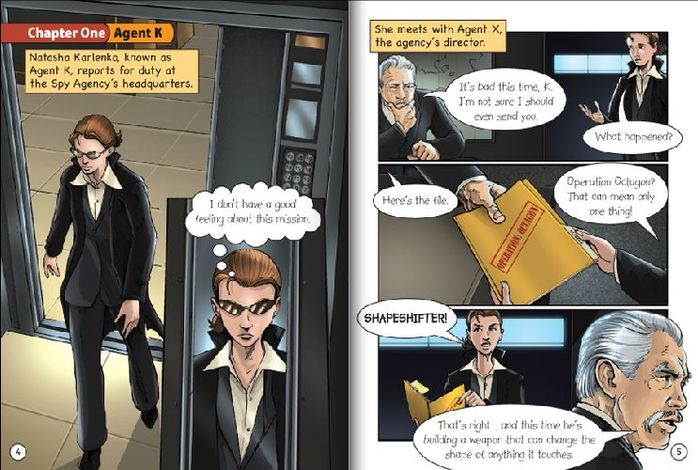

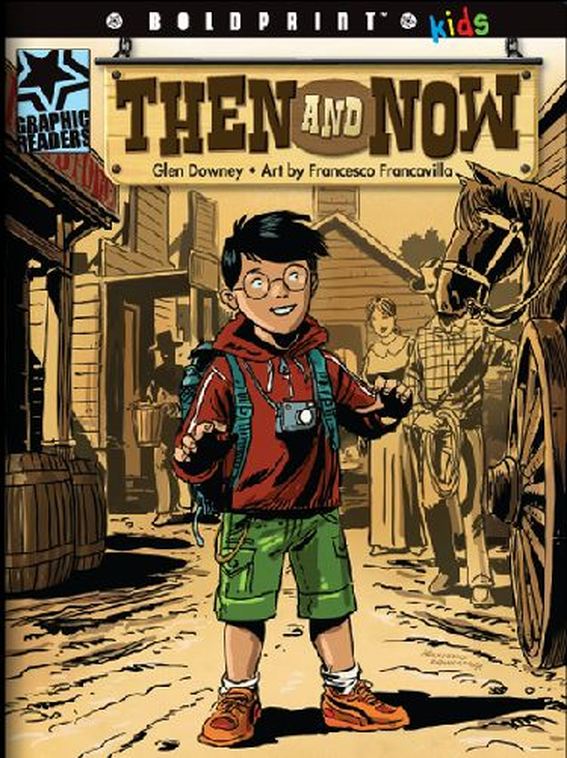

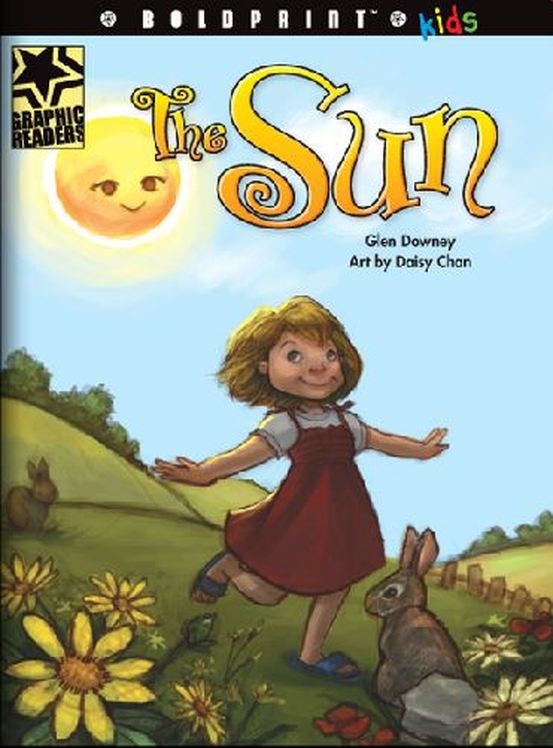

Boldprint Kids Graphic Readers Help K-3 Students Learn Math Math is one of those subjects that students will make judgments about pretty early on in their academic career. It's not so much the math they make a judgment about--it's their ability to do math. It's sad when kids make these kinds of judgments about themselves early on, or when parents makes such judgments for them (e.g. "Don't worry, I wasn't very good at math either"). A great resource for the K-3 math classroom is the Boldprint Kids Graphic Readers series from Rubicon/Oxford. These readers speak directly to the most common curricula found in the primary grades. What's the Problem, for instance, looks at rudimentary problem solving of the sort that students in Grade 3 would engage in, while Hoop Shot helps to support students doing the measurement unit in Grade 1. Indeed, all of the readers in the series are designed specifically to provide a visual narrative that helps to support a child's development in one of their core subject areas, like mathematics, science, and social studies. You can find this award-winning series at their official website. If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy:

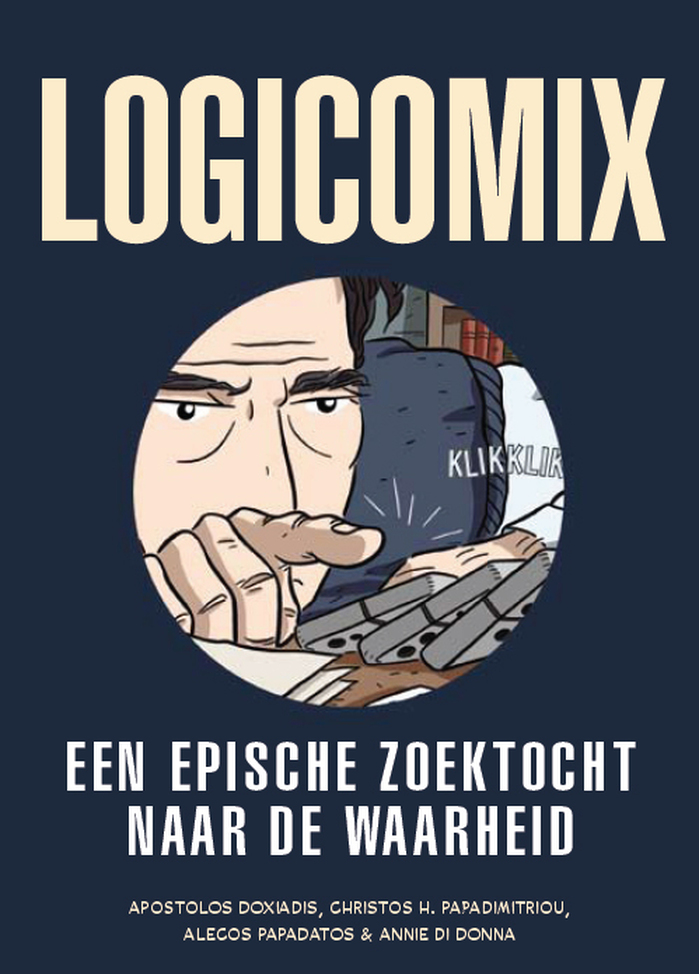

If you're thinking that comics and graphic novels are only for the English or Social Studies classroom, think again. One of the best graphic novels you can get your hands on is actually about the history of mathematics. In Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth, Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H. Papdimitriou examine the life of Bertrand Russell as well as some of the most important and influential mathematicians and thinkers of the 20th century. The book isn't only about Russell's life as a mathematician and pacifist, however, but of the group of artists and illustrators trying to put it all together, and so the narrative switches back and forth between the actual present, the present of the narrative, and the recollections of Russell's own past, including his work with Alfred North Whitehead on Principia Mathematica. Of special interest to math educators will no doubt be the part of the story when Russell's attempts to establish a progressive school for young people that does not subscribe to traditional models. Needless to say, things go horribly awry when the students realize that they are not bound by traditional rules! The book was #1 on the New York Times bestseller list for Graphic Novels and received widespread critical praise. Although it plays fast and loose with historical accuracy at times, it is thoroughly engaging, and a great way to show students how the math they are studying didn't just fall out of the sky one day. It came from the likes of the mathematicians and thinkers shown below! If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy: Comics in Education Presents: English Reading Lists that Work -- Culture, Race and Identity

5/13/2014

This is the first in a series of posts that are intended to give English educators some new ways of thinking about how to incorporate graphica into their curriculum. One way of making inroads with colleagues who are resistant to visual narrative in the curriculum is to show them how these works speak to, reinforce, support, augment, and otherwise work well with canonical literature dealing with similar concepts or themes. As you read these posts, please feel free to send me your ideas. I'd love to publish them on our site! Reading List

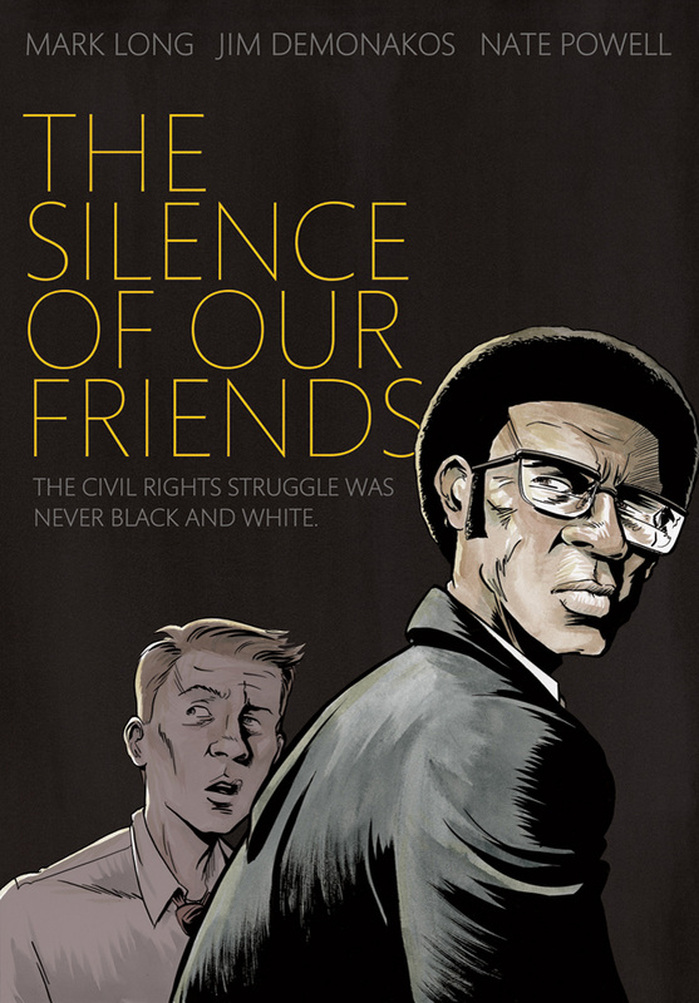

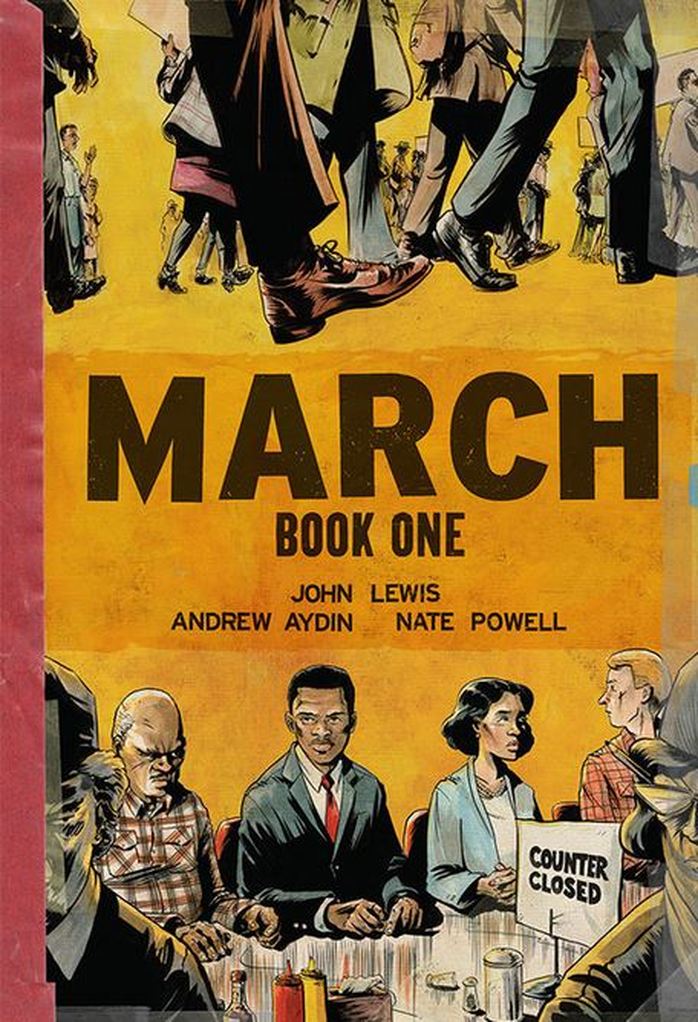

Rationale I like this roster of text choices, not only because the two novels and the choreopoem are written by women, but because the list will present students with engaging and challenging material. This is especially true of both Beloved and For Colored Girls and teachers would be well advised to ensure in advance that their students can handle the issues presented in these works. I love the addition of The Silence of Our Friends, a semi-autobiographical work that looks at race relations in Texas circa 1967, with a white family from a notoriously racist neighborhood befriending a black family living in one of the the city's poorest wards. They come together when five black students are unjustly charged with the murder of a policeman. The other graphic title I've included here was written in 2013 and was accorded numerous honors that included consideration for Graphic Novel of the Year. That's March, Book 1, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, who also happens to have illustrated The Silence of Our Friends! Of course, the amount of time that you have with your students and the specific demands of your curriculum will decide whether you can take an approach as suggested by the above list. However, we shouldn't underestimate the extent to which 21st-century students appreciate a curriculum that makes sense to them, and seems to be put together with the express purpose of fully and authentically developing their understanding of a particular issue or theme. If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

When I want a full-on, comic convention experience, the Toronto Fan Expo absolutely does it for me. It's a great event, and I'll never forget how my kids bounced off the walls in 2012 after getting to have their picture taken with this guy you may have heard of named Stan Lee. When I'm looking for something more intimate, however, it's hard to beat the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Taking place over the course of a week, it brings some of the finest creators working in visual narrative to Canada's largest city. For those of you unfamiliar with TCAF, it's put on by The Beguiling and the Toronto Public Library and is described by organizers in the following way: It is a week long celebration of comics and graphic novels and their creators, which culminates in a two-day exhibition and vendor fair featuring hundreds of comics creators from around the world. Other Festival events include readings, interviews, panels, workshops, gallery shows, art installations, and much more. Since 2009, TCAF has been held at Toronto Reference Library in Toronto, Canada, and presented by Toronto Public Library. Whether you're watching a great panel taking place at the Marriott Hotel, listening to a talk being given at one or more locations in and around Bloor and Yonge, or strolling the floors of the Toronto Reference Library where publishing houses are showcasing their wares, you'll notice that the TCAF has something a typical convention lacks... Intimacy. At TCAF, visual narrative devotees can walk up and talk to some of their favourite comics creators--not just walk up and say a quick hello, but have an actual conversation. Chester Brown won't just sign your prized copy of Louis Riel or Ed the Happy Clown for you -- he'll actually be interested in having a bit of a chat. And for the more conservative-minded among you who don't want the craziness of a full-on convention, you can be rest assured that things never get too out of hand at TCAF. After all, it takes place largely in a library where some patrons are--get this--just there to use the library! The TCAF is a festival that just seems to do things the right way. Even the Kickstarter campaign to help fund the Doug Wright Awards was excellent this year. Hats off to Brad Mackay, by the way. If you were around this past Saturday you could have attended the awards ceremony because it, like everything else at the TCAF, comes with the same price tag. Yes...that's right folks. It's absolutely free. Therein, perhaps, lies at least some of the magic that is the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

There are very few English teachers out there in the K-12 education system who haven't come across this question, thought about it, and formed a professional opinion. The question, after all, is simple: Should we use comics to teach Shakespeare? As it turns out, however, the question itself is the problem. It's framed in much the same way that we frame other large questions about education:

Such questions are often intended to get us to reconsider our fundamental thinking about education. When we casually answer them with "yes" or "no," however, we're stepping on dangerous ground. Is it really possible that choosing one side of this binary is correct in every possible context? When it comes to using comics to teach Shakespeare, I've come across two very strong opinions. Some will say that graphic versions of Shakespeare's plays should be used in the K-12 classroom-- that we need to cast off our reservations about them and get with the times. Others will argue--often a bit more vehemently--that graphic versions shouldn't be used in the K-12 classroom (unless we're trying to enlighten reluctant or struggling readers). You see, when questions like "Should we use comics to teach Shakespeare?" are asked, they are bound to provoke responses that are either protectionist or dismissive. Here's a better question, then:

We talk a lot about backwards design in education, and about ensuring that the goals of a given lesson, unit, or course are firmly in mind before we start. If so, why is there a debate about whether or not we should use comics to teach Shakespeare? Do comics or graphic novels help us to achieve our goals in a particular lesson? If so, we should use them. If not, we shouldn't. If I want my students to read a passage from Twelfth Night or The Tempest, try to figure out what is happening, and consider how Shakespeare's language creates a picture in their minds of the events that are unfolding, it wouldn't make sense to use a graphic version of that scene. After all, I am wanting them to imagine the visual in the absence of looking at something visual. Using a graphic version of the scene in this instance would therefore be counterproductive and silly. If, however, I want the students to build their vocabulary my marrying the verbal and the visual, or discuss the relationship between what a character is saying in a given scene and how that character might look, act, or appear on stage, then using a graphic version of the scene is perfectly appropriate. Watching the same scene on film also makes excellent sense. The long and short of it is that when it comes to teaching Shakespeare using visual narrative, we have to have good reasons. We should use graphica when it supports our students' fuller appreciation and understanding of Shakespeare and his work, and use something else when it doesn't. If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy:

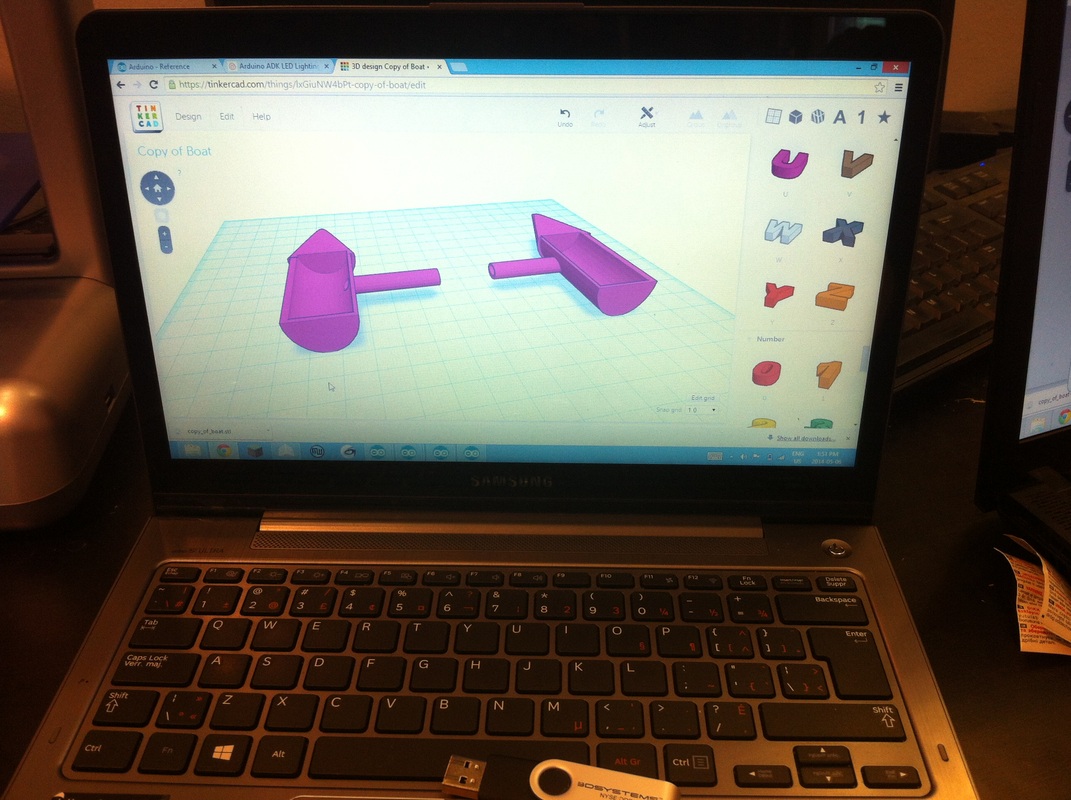

Each year, students at The York School in Toronto undertake Challenge Week excursions, travelling all over the GTA and across Canada to engage in experiential learning activities. Last year, I had a group at The Brickworks in Toronto (where TYS has a classroom) for a week-long experience called “Write of Passage.” It featured aspiring Grade 10 writers working with experienced poets, food authors, and playwrights. This year, I’m with a group at Maker Kids in Toronto, an organization that allows students to get hands-on experience building just about anything they can think of. Located at 2241 Dundas Street West in Toronto, Maker Kids is a unique space, as its website notes: MakerKids is one of the only makerspaces for kids in the world. It’s a non-profit workshop space where kids can learn about and do things like 3D printing, electronics, and woodworking. We offer workshops, camps, afterschool programs and more at our location in Roncesvalles in Toronto, and participate in external events in the GTA and beyond. We enable kids to build their ideas with real tools and materials; our goal is to inspire and empower kids to think, design, experiment and create. When we asked students what they wanted to make, it didn't take long for one of the groups to say "Hovercraft." The short video below shows a 3-D printer having a go at one of the casings for the high speed lift propeller. What is so impressive about Maker Kids is the visual and tactile learning environment in which students are immersed. Here the goal is to have them dream big and to ask for anything that can help bring their dream to reality. On just the first day of our excursion, our students were imagining designing everything from piano gloves to iPhone accessories to hovercrafts and miniature helicopters. Important in fuelling this hands-on, tactile learning experience is all of the signage around the space that encourages students to pursue their ideas. It strikes me that this visual stimuli – not just the encouraging posters but all of the equipment that surrounds them – does something for the students that is not unlike what I see comics and graphic novels doing for reluctant and struggling readers. It gives them a more immersive kind of experience and helps to reassure and encourage them in their process of attempting to make meaning from their experiences. Maker Kids has a wealth of programs for kids but also sets aside time for parents and educators. For more information about their programs, you can check out their website at www.makerkids.ca.

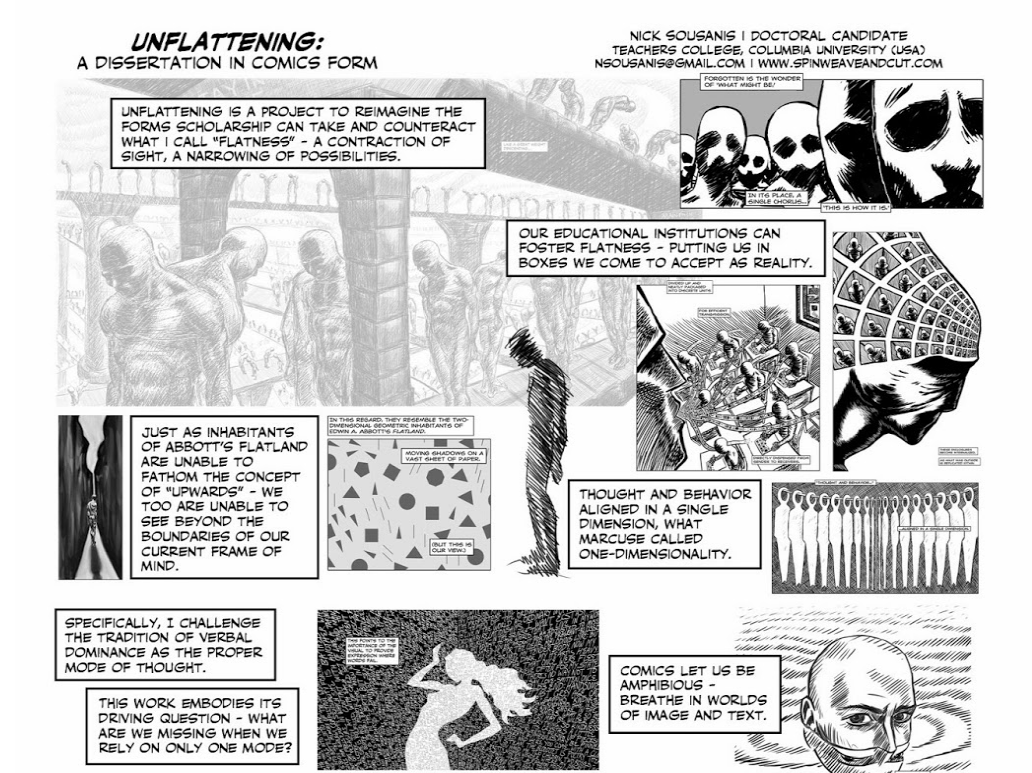

The world of academia just got a little less flat. While everyone was wishing one another a happy #StarWarsDay yesterday or enjoying #FCBD (that’s Free Comic Book Day for those who don’t get out much) the day previous, I'm guessing that considerably fewer were paying attention to what Nick Sousanis was doing at Teachers College, Columbia University. He was defending his doctoral dissertation, written entirely in comic book form. Writing a dissertation is challenging enough, but what Nick has undertaken is a step beyond challenging. His dissertation, “Unflattening: A Visual-Verbal Inquiry into Learning in Many Dimensions,” uses visual narrative in a way that may cause a few traditionalists to raise a Spockian eyebrow, but his work and its particular form are an important contribution to academia. As Sydni Dunn noted in her Chronicle article on Nick's dissertation earlier this year, his work is being recognized by other academics as part of an important development in the evolution of research at the doctoral level: Sousanis’ work is just one example of this evolution, says Sidonie Smith, director of the Institute for the Humanities at University of Michigan, who is a former president of the Modern Language Association. Smith has also seen dissertations presented as series of articles, as public blogs, and as interactive digital projects, to name a few. In earlier blogs I’ve provided K-12 teachers with a a rationale for comics in education and in other posts have discussed both why we should teach comics and how we can explain to fellow colleagues and administrators the reason they should be included in the curriculum. Nick’s work should help to make such conversations easier. Next time someone balks at your suggestion of choosing The Silence of Our Friends or Boxers & Saints for a unit on cultural conflict because "comics aren’t academic," show them Nick’s dissertation and tell them that the 21st century has arrived and that they should put down their copy of Martin Chuzzlewit and come outside and play!

A must-see for any fan of comics and cartoons! If you happen to be making your way this summer either to Pittsburg or San Francisco, there are a couple of very special museums you won't want to miss. ToonSeum and the Cartoon Art Museum are institutions dedicated to showcasing and celebrating the history of visual narrative. Here are the mission statements of the two museums and some important information for potential visitors. ToonSeumThe mission of the ToonSeum is to celebrate the art of cartooning. Our goal is to promote a deeper appreciation of the cartoonists and their work through hands-on workshops, community outreach, cartoon-oriented educational programming, and exhibitions of original cartoon art. The museum opens at 10:30 am from Wednesday to Sunday, and admission for 13+ is only $8.00. From April 11 to June 30, you won't want to miss their Golden Legacy exhibit, featuring the work of the Little Golden Books line of picture books. For a short article on the current exhibit, click here! The Cartoon Art MuseumThe Cartoon Art Museum’s key function is to preserve, document, and exhibit this unique and accessible art form. Through traveling exhibitions and other exhibit-related activities — such as artists-in-residence, lectures, and outreach — the museum has taken cartoon art and used it to communicate cultural diversity in the community, as well as the importance of self-expression. As the website notes, the Cartoon Art Museum (CAM) hosts dozens of events throughout the year that includes signings, lectures, and special exhibits. Its current exhibit, running from April 26th to August 24th is called "Pretty in Ink" and features the work of comics herstorian, Trina Robbins. Having just enjoyed free comic book day here in Oakville, I think there's no better way to end it than celebrating those who look to preserve the proud legacy of visual narrative!

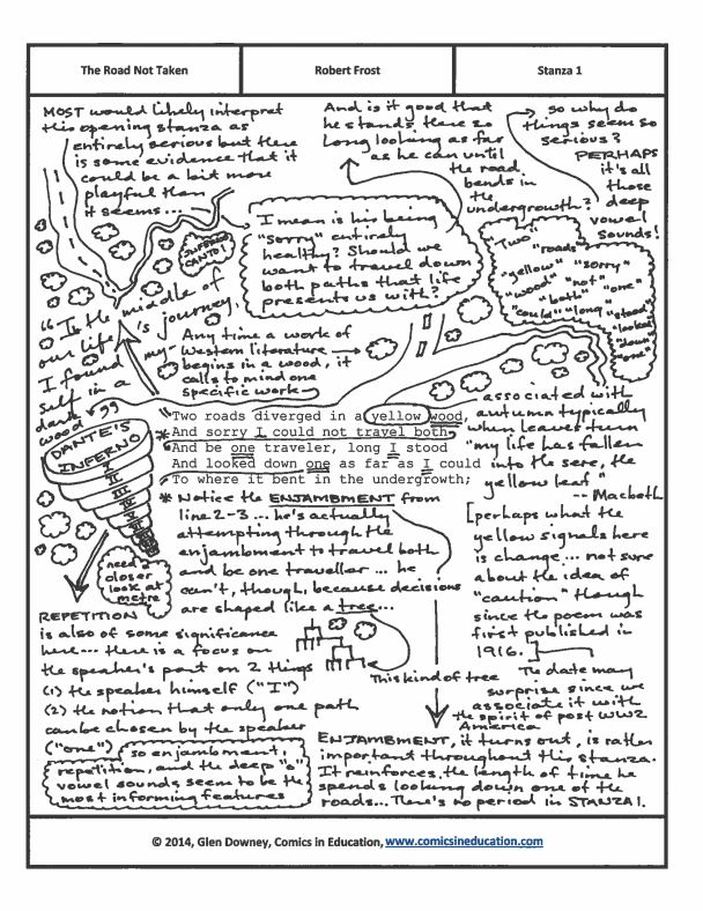

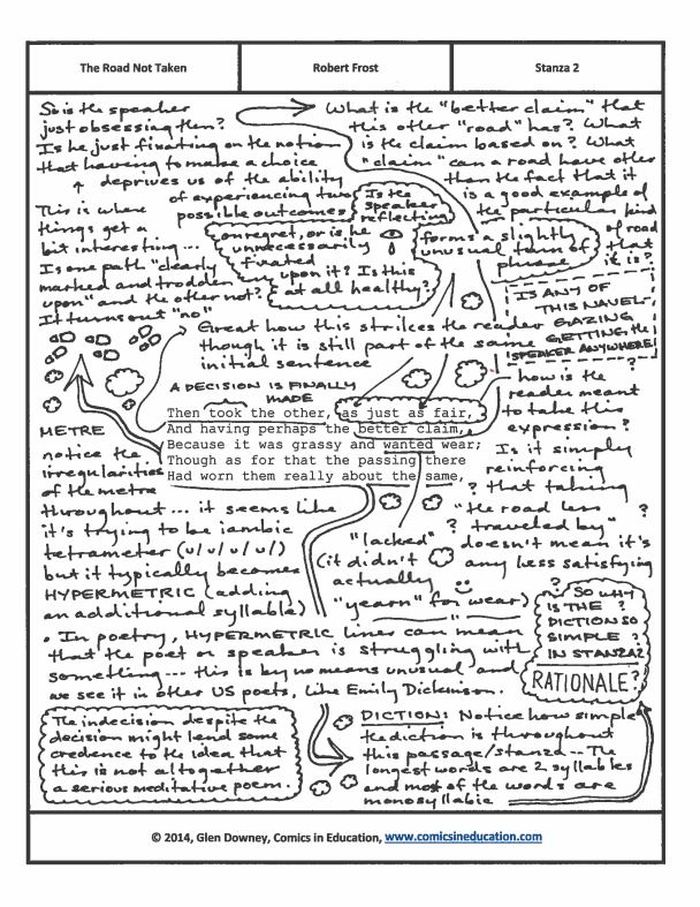

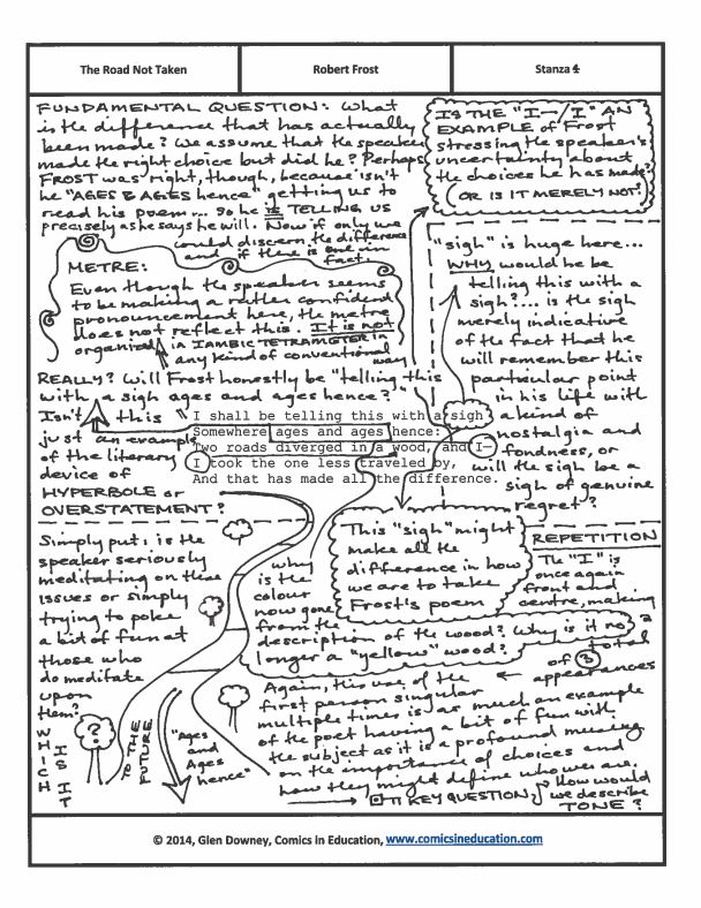

Would you like to see more of these? With the great response we've received to our Visual Brainstorming posts (check out our April, 2014 posts especially), Comics in Education is wondering whether teachers might be interested in purchasing digital downloads of professional brainstorming notes based on poems and other short works most commonly taught in schools. As the school year draws to a close and educators are looking for materials for next year, these might prove to be a nice addition. I'm thinking that a fair price is 99 cents and they're better for you than a McDonald's hamburger or 1/5th of a Starbucks White Chocolate Mocha. Okay, maybe not the mocha. Anyways, take a look and see for yourself. As you can see from the images below, a lot of time and care go into each poem, with the poem itself being broken down stanza by stanza. So, if you're interested, just let us know at [email protected] or fill out a contact form here. We look forward to hearing from you! |

Glen DowneyDr. Glen Downey is an award-winning children's author, educator, and academic from Oakville, Ontario. He works as a children's writer for Rubicon Publishing, a reviewer for PW Comics World, an editor for the Sequart Organization, and serves as the Chair of English and Drama at The York School in Toronto. If you've found this site useful and would like to donate to Comics in Education, we'd really appreciate the support!

Archives

February 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed