There are very few English teachers out there in the K-12 education system who haven't come across this question, thought about it, and formed a professional opinion. The question, after all, is simple: Should we use comics to teach Shakespeare? As it turns out, however, the question itself is the problem. It's framed in much the same way that we frame other large questions about education:

Such questions are often intended to get us to reconsider our fundamental thinking about education. When we casually answer them with "yes" or "no," however, we're stepping on dangerous ground. Is it really possible that choosing one side of this binary is correct in every possible context? When it comes to using comics to teach Shakespeare, I've come across two very strong opinions. Some will say that graphic versions of Shakespeare's plays should be used in the K-12 classroom-- that we need to cast off our reservations about them and get with the times. Others will argue--often a bit more vehemently--that graphic versions shouldn't be used in the K-12 classroom (unless we're trying to enlighten reluctant or struggling readers). You see, when questions like "Should we use comics to teach Shakespeare?" are asked, they are bound to provoke responses that are either protectionist or dismissive. Here's a better question, then:

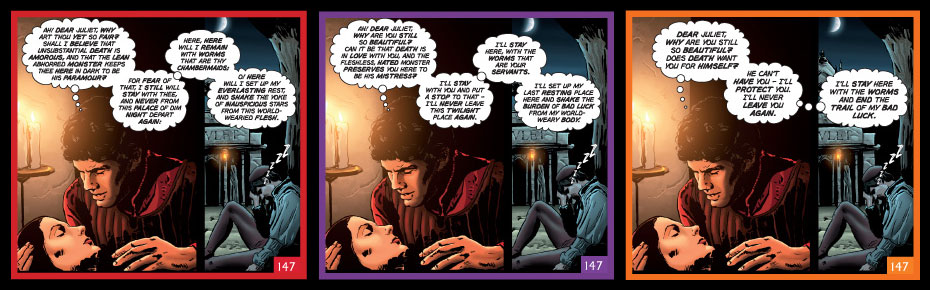

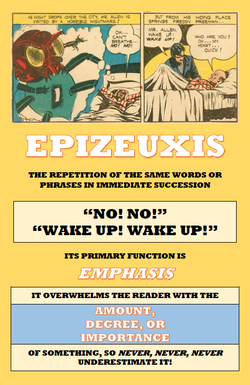

We talk a lot about backwards design in education, and about ensuring that the goals of a given lesson, unit, or course are firmly in mind before we start. If so, why is there a debate about whether or not we should use comics to teach Shakespeare? Do comics or graphic novels help us to achieve our goals in a particular lesson? If so, we should use them. If not, we shouldn't. If I want my students to read a passage from Twelfth Night or The Tempest, try to figure out what is happening, and consider how Shakespeare's language creates a picture in their minds of the events that are unfolding, it wouldn't make sense to use a graphic version of that scene. After all, I am wanting them to imagine the visual in the absence of looking at something visual. Using a graphic version of the scene in this instance would therefore be counterproductive and silly. If, however, I want the students to build their vocabulary my marrying the verbal and the visual, or discuss the relationship between what a character is saying in a given scene and how that character might look, act, or appear on stage, then using a graphic version of the scene is perfectly appropriate. Watching the same scene on film also makes excellent sense. The long and short of it is that when it comes to teaching Shakespeare using visual narrative, we have to have good reasons. We should use graphica when it supports our students' fuller appreciation and understanding of Shakespeare and his work, and use something else when it doesn't. If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Glen DowneyDr. Glen Downey is an award-winning children's author, educator, and academic from Oakville, Ontario. He works as a children's writer for Rubicon Publishing, a reviewer for PW Comics World, an editor for the Sequart Organization, and serves as the Chair of English and Drama at The York School in Toronto. If you've found this site useful and would like to donate to Comics in Education, we'd really appreciate the support!

Archives

February 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed